|

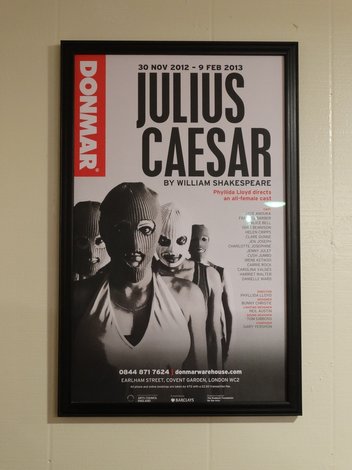

One of the great things about Facebook and social media is that it provides an informal record of what you did and when you did it. According to the Book of Faces, January 13th has, personally speaking, been a fairly eventful date for me. Two years ago, it marked my acquisition of the coolest wine-storage system in all of Henrietta, NY (see photo below). Six years ago, it marked the date of my application to the graduate program that I would eventually attend. Four years ago, it was the date that I returned from my first trip to London, which included (on January 12th) what was, to date, the best Shakespeare Production I had ever seen--Phyllida Lloyd's all-female cast production of Julius Caesar, set in a women's prison. On January 13th, 2017, after four years on the outside, I was thrilled to once again go back to prison--this time, in New York City. Before I get into the details of the show I saw THIS weekend, I want to take a moment and set the stage. The first time I saw this cast/director was four years ago, at the Donmar Warehouse.  At that show, the set was the first thing that caught my attention. There was a sort of wire-like material on the railings in front of us. There were musical instruments, television screens and—the part I was most interested in—the performance space seemed to occupy three potential levels—the main acting space below us, some platforms and catwalks at eye level, and another set of catwalks above us. I thought it would be absolutely fascinating if they ended up using all three—I thought it would make the show feel like it was going on all around us. I couldn’t figure out how they would utilize the upper catwalk, however. When a random light from above caught my eye in the middle of the show, I looked up and realized that prison guards were patrolling the upper catwalk—and that we, the audience, were cast as inmates (the always important mob in Julius Caesar). The prison setting helped to create a constant sense of real danger that I've never seen in a production of Caesar before. Scenes that I had previously only seen delivered as rhetorical moments were now loaded with tension and the potential for violence. One of these scenes is one often played for comedic effect, such as Caesar's wish in 1.2.190-195 to only have "men about me that are fat." Caesar mistrusts thin men like Cassius, who have "a lean and hungry look." Of course, this scene is a way for Caesar to both poke at Cassius and highlight Cassius' ambition. In this production, Caesar force-feeds Cassius a Krispy Kreme donut, while Cassius, aware of the hierarchical nature of the prison inmate power system, accepts the abuse with a look of utmost rage on her face. That sense of real danger also came through in the inspired decision to have Antony begin the “Friends, Romans, Countrymen” speech in a prone, passive position. The prison population is one of the few modern parallels we have to the violence of the Roman mob as depicted in the play, and setting the play among that population made the production feel more dangerous and less “history channel.” This prison violence was sudden and unexpected in a play that features perhaps the most predictable violence in all of Shakespeare. Shakespeare in prison settings is not exactly a new concept, but what Lloyd does so wonderfully here is to create a more serious take on the prison/Shakespeare concept. I've seen it done before. HBO's show Oz, in its final season, featured the inmates putting on a production of Macbeth. The pseudo-documentary Caesar Must Die offers a treatment of the same play, with interviews mixed in featuring Italian inmates (some real and some actors). But while Oz was going for comedic effect (every character to be cast as Macbeth died by the end of the episode) and Caesar Must Die was going for an artistic approach, Lloyd's play was authentic. This could have been a real prison populated by real inmates. The prison motif—particularly the big reveal at the play’s end that the woman playing Caesar was one of the guards rather than one of the inmates—also served to address my biggest fault with Julius Caesar (the play). One of the reasons I’ve never been overly fond of the play was that the title character is dead and gone by Act Three, yet the play continues (largely in dragging conversations between an increasingly whiny Cassius and an ever more pitiful Brutus). It is mentioned in the play that the conspirators see Caesar’s ghost as they prepare to kill themselves, but I’ve never seen that idea expanded upon so thoroughly as is was in Phyllida Lloyd’s production. After Caesar’s appropriately grisly prison murder, she routinely begins popping up where we least expect her. When the cloaked standard bearer is shot dead and stays prone on stage, we don’t give it a second thought—long minutes later, in a quieter moment, however, the standard bearer stands and drops her cloak, revealing herself to be Caesar’s ghost. Caesar never quite vanishes after her death—moving around the background, glaring at the conspirators and, in one fantastic moment, Caesar mans the drums, providing the drum-beat sound effects for the gun shots that take the lives of the lesser conspirators. The ghost of Caesar is present in this production in a way that I’ve never seen before, and when we find out at the end of the play that Caesar was the only prison guard in this “play”, it adds a whole new dimension to how we understand the almost omniscient constant presence. The play is rehabilitative in part—the inmates are clearly dejected that their acting time is over, and despite this, they fall in line to be taken to another part of the prison—but guard/Caesar also perpetually re-establishes authority. It’s a warning that they are always being watched, and that insurrection (i.e.- prison riot) can only end in the deaths of those who lead such insurrection.

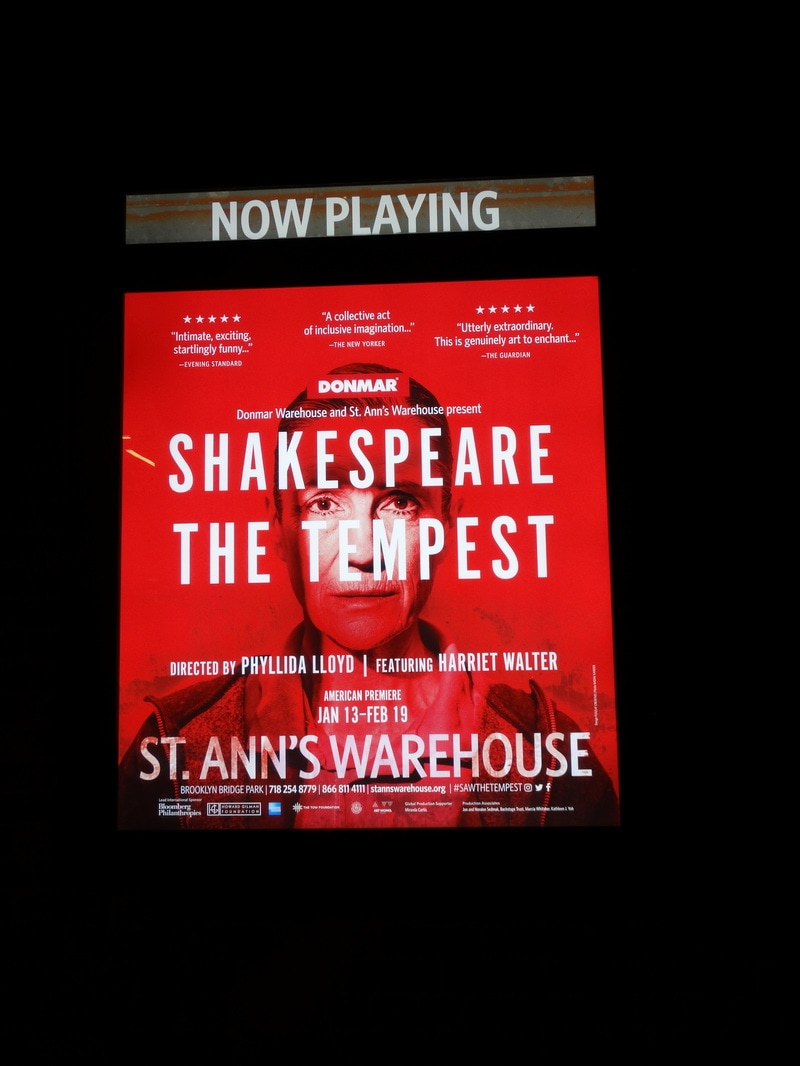

I called my "theater adventure" cousins (Brenna, Al, and Katie--we had forged our NYC theater adventuring back in 2013 with a trip to see Alan Cumming's one man Macbeth. See photo below of me with Cumming. Then be jealous, haha), and we started planning our next adventure. This trip would be split on my end, half with the biological family crew and half with my theater family. My friends Jilly and John Christensen moved to NYC a year or so ago, and graciously offered to host my weekend visit. Jilly was the director of my first ever show as an actor (I joke about how she took my "theaterginity") and she showed me around her new city with a grand tour, which included an amazing view of the city and multiple trips to the most mouth-watering pizza places. But, as fun as the touring was, I didn't come to NYC to eat pizza (well, not just to eat pizza). I came to NY to return to prison. The venue at the St. Anne's Warehouse is just stunning. The view from their patio is worth the price of admission alone (and on that point, the price point on this show was absurdly low. I snagged primo seats and the tickets were under $60 each after fees). This theater is tucked right under the Brooklyn Bridge in the DUMBO neighborhood. As the start of the show arrived, I admit that I started to get a little nervous. The bar had been set so high by the Donmar production in 2013. What if this show seemed derivative? What if it not only didn't live up to the prior show, but also somehow tainted my feelings/memory about that earlier experience? I needn't have worried. The easiest way to sum it up is with the words I said to my cousin Katie immediately after the curtain call. "They did it again!" I could literally write a blog post on each of the major actresses in this production. There was not a weak performance in the entire show. That said, this is already likely to be one of my longest blogs, so I will try to limit myself to just the performances that drew strong reactions from me personally. Jade Anouka's Ariel was absolutely flawless. The character was simply alive on the stage, and Anouka's performance gave Ariel the sort of mercurial presence that is often gilded over with a more waifish/other-worldly aesthetic. The Ariel of this production was anything but otherworldly. She was rooted firmly in modern culture and this was reflected in the way Anouka deployed a variety of dance and musical genres. It is rare for a show to add to Shakespeare, because the modern additions often feel out of place. Anouka's Ariel shifted from a more R & B sound to an island beat, to an absolutely haunting "Full Fathom Five" with so much skill that anyone not already familiar with Shakespeare's play would likely have difficulty figuring out which music was from Shakespeare's Tempest and which was added by the inmates of St. Anne's/Donmar. Anouka's costume changes were frequent and effective, and she had a particular talent for moving about the venue unseen so that it appeared as if she could transport herself via magic (there were no secret passages in this venue, so movement happened in plain sight). Finally, she often moved to a sort of "crinkle" sound (I'm not entirely sure what to call it, to be honest), which indicated her magic at use. It was a nice touch, and allowed Anouka to continue to use her movement (a definite strength) to portray magic. Her character reminded me of Morgan Freeman's character in The Shawshank Redemption. The skills at her command seemed to be part magic and part "being a person who knows how to get things." The three clowns of the show, as is usually the case with The Tempest, were favorites. Jackie Clune and Karen Dunbar had brilliant chemistry as Stefano and Trinculo (respectively). They even managed to add a bit of power-hierarchy to the show (via their underpants) as Clune's British Stefano took command over Caliban and Dunbar's Scottish Trinculo. There wasn't really any particular moment that these characters had on stage that stood out. It was more that these characters truly seemed to be having fun with each other in a way that could not be faked. Sophie Stanton's Caliban was another revelation. She played the role in a far more reserved tone than what I'm used to seeing. It worked wonders for this production though, as it kept the comedic spotlight on Clune and Dunbar, and helped to build to another moment that I'm going to discuss a bit below. On a total side note, Clune and another performer (Liv Spencer) came out to the lobby while we were still milling about. They were both extremely warm when I gushed a bit about this show (and the one I saw four years prior). Clune broke my heart a bit with her first question for me though (she asked if I had seen their 1 Henry IV. Still kicking myself over that one). Leah Harvey's Miranda and Sheila Atim's Ferdinand, the young couple at the center of the romantic plot, were energetic and charming. Atim brought an awkward but roguish charm to Ferdinand coupled with a clear sense that this inmate had NO idea what he was doing, either in her interactions with Prospero or her flirtations with Miranda. The focus of Ferdinand's love, Miranda, was delightfully petulant, walking a line between being the dutiful daughter and being independent and in love, which was, of course, the transition being explored both in this production and in Shakespeare's play. The energy of this pair (combined with the similar energy of Ariel, Trinculo, Stefano and more) set off the sometimes dour, perpetually reflective aspect of Dame Harriet Walter's Prospero. It also made this two hour play fly by, with the well-deserved standing ovation seeming to come right on the heels of Walter's opening monologue. The little bit of acting that I have done has mainly been on the "bit player" end of the dramatis personae (case in point, when I was in the Tempest, I played an amalgamation of three different characters. All three of those characters were cut from Lloyd's production). As such, I tend to really watch how the smaller roles are functioning in the play. As I was doing that during this production, I picked up on something astounding, and that I want to be sure to mention here. The sardonic guards, Liv Spencer in particular, were one of the highlights of the play for me. Not because of the dry humor and the insults. While funny, those additions would not have stood out if they just seemed like a way to move the plot forward or reinforce the prison theme. No, what hit me, initially as I watched the play and then with full force as I was processing it the following day, was the realization that Spencer and the other guards were the island. They led the inmates this way and that in a seemingly random pattern. They took these pampered nobles and removed the comfortable notion of control that they valued. This metaphor would have been so easy to "over-do," but Spencer presented it with such deft skill that I almost missed it at first. It must take extraordinary skill to be both comic relief and the metaphorical representation for the entire concept of the production. The more I work through what I saw, the more I feel that Spencer's performance was one of the highlights for me.

I want to culminate this absurdly long blog post by mentioning two key scenes. These are the two moments that really made the play for me. The first happened during the wedding celebration wherein Prospero "conjured" up spirits to entertain Miranda and Ferdinand at their wedding. The spirits, disguised prisoners wearing masks made out of cardboard toothpaste boxes, played music and followed it up with a lively and energetic dance. The masks matched the rest of the props, which were all constructed from garbage and the sorts of things that might be found in a prison. The "wedding feast" was a mishmash of food items that might be found in a prison commissary, including a cake, which appeared to be a massive stack of granola bars. As the dancing commenced, large white floating balloons were brought out and placed around the stage, each anchored to a water bottle. Suddenly, with a wave of Prospero's hand, every inmate stopped in awe as video images were projected onto the balloons. These were images of the outside world. Nature, cars, fast food (a McDonald's logo got a raucous cheer from the inmates), and more. In a play defined by prison-issue costumes and props made from leftover garbage, this singular moment was as beautiful as it was unexpected. In the midst of prison life and prison production values, the show dropped a little bit of magic for just the briefest of moments. A distraught Prospero, in perhaps Walter's finest scene, pops each one of the balloons. In this production, she doesn't stop the pageant because of a sudden remembrance of Caliban's forthcoming betrayal. Here she stops it because she is projecting for the gathered inmates that which she cannot have for herself--hope.

Prospero is not alone in her hopeless state, however. At the end of the play, in an incredibly powerful scene, Walter's Hannah character sits on her prison bed, reading. One by one, each of the other prisoners appears in civilian clothes, offering final words of thanks to the woman who got them through to their release dates. It is a moment that is as heartbreaking as it is uplifting. Hannah has done good work for these women and increased her own suffering as a result (getting close to people she knows she will lose). But there is an even more subtle moment of sadness and loss presented in this final scene. Caliban, revealed to be Prospero's cellmate, is also still in prison. She spends the final scene vacuuming Prospero's cell. Casting Caliban as another "lifer" brings new light to an old (and favorite) passage from this play. I've always loved Caliban's lines to the clowns about the sounds of the island: "Be not afeard; the isle is full of noises, Sounds and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not. Sometimes a thousand twangling instruments Will hum about mine ears, and sometime voices That, if I then had waked after long sleep, Will make me sleep again: and then, in dreaming, The clouds methought would open and show riches Ready to drop upon me that, when I waked, I cried to dream again." It's a surprising moment of poetry from an otherwise bestial creature. I love this passage because it always drives home the idea that everyone has that place/thing that they love and can describe better than anyone else. No matter how bestial Caliban is, he is of the island, and he loves it as a result. But in this production, I can't help but think that this speech is now reflecting the institutionalization of inmates (i.e.: when inmates are in prison for so long that they are afraid of living anywhere else). Which brings us back to the prison theme. They did it again. They used this concept to mine a VERY frequently performed work of Shakespeare for brand new angles and ways to get at the text. All of what they found and presented on that stage is in that play. We've just missed seeing it (or seeing the potential for it) for a few centuries. It's like the balloons: pure magic. Next week's blog WILL be shorter. I'm going to write a bit about a pedagogical technique I've been playing with for the last few years. Until then, if you're able, go see this play (it runs through February 19th at St. Anne's Warehouse in Brooklyn). It is so worth it. Ticket info Harriet Walter's new book about her performance in this trilogy The trilogy of plays involved collaboration with the Clean Break Program. Be well, Scott

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Author

Welcome to the "Blue Collar Scholar" blog at TheRenaivalist.com (i.e. Scott O'Neil's personal and professional blog). Archives

April 2018

Categories

All

|

"Neque enim is verus est habendus orator, qui bene scit dicere, nisi et dicere audeat."

“No one who knows how to speak well can be considered a true orator unless he also dares to speak out.”

Lorenzo Valla, De falso credita et ementita Constantini donatione 1440

“No one who knows how to speak well can be considered a true orator unless he also dares to speak out.”

Lorenzo Valla, De falso credita et ementita Constantini donatione 1440

RSS Feed

RSS Feed