|

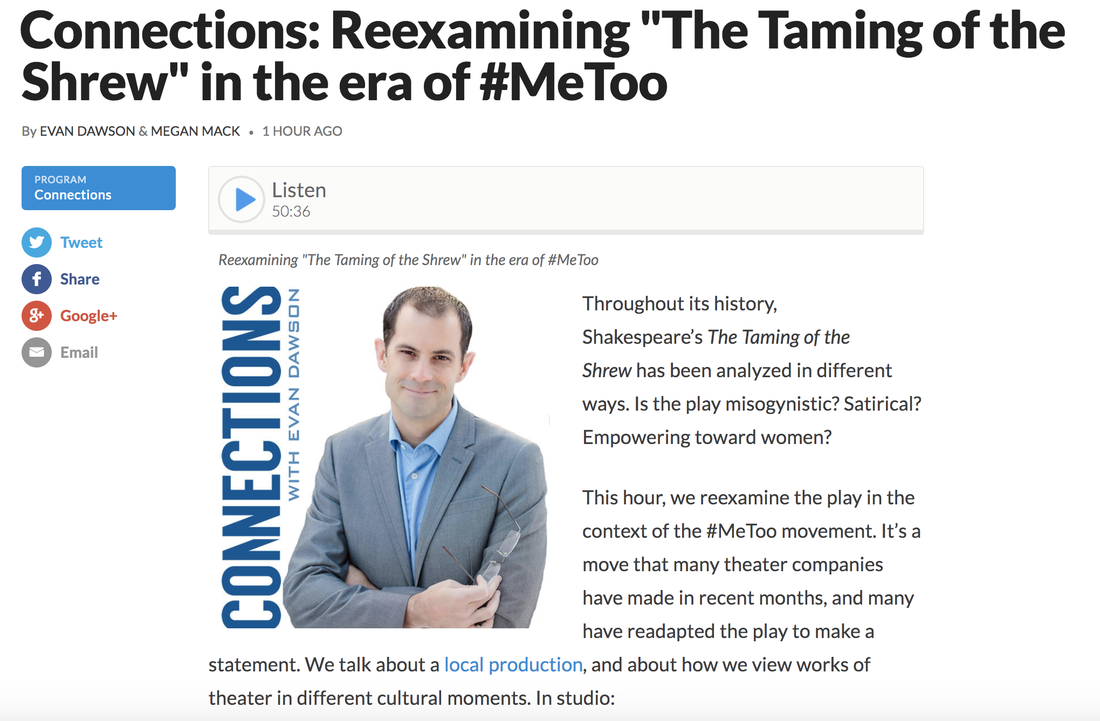

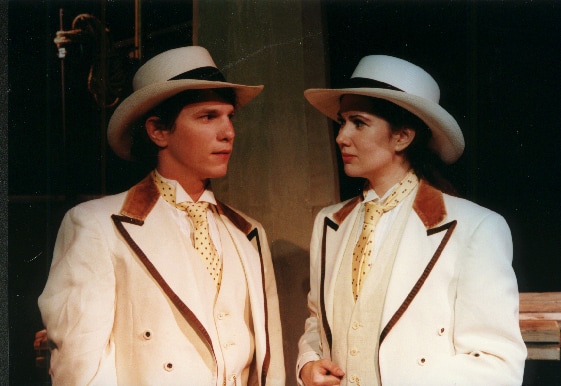

Just a quick post to let y'all know that I was on Connections with Evan Dawson on NPR this afternoon. Evan had myself (in my role as a dramaturge), WallByrd artistic director Virginia Monte, and performer/scholar Jamie Tyrrell on the show to chat about issues related to putting on plays like The Taming of the Shrew in the era of the #MeToo movement. Jamie, Virginia, and I started the conversation 20 minutes before even going up to the studio, and continued the conversation long after the show had ended (I think the ladies at the front desk of WXXI thought we had moved into the lobby permanently, haha). See below for a link to listen to the show, if you are so inclined, and a couple of photos from the visit! Now back to the dissertation revision! Be good! Link to the show: HERE

Or go to the web address directly: http://wxxinews.org/post/connections-reexamining-taming-shrew-era-metoo

3 Comments

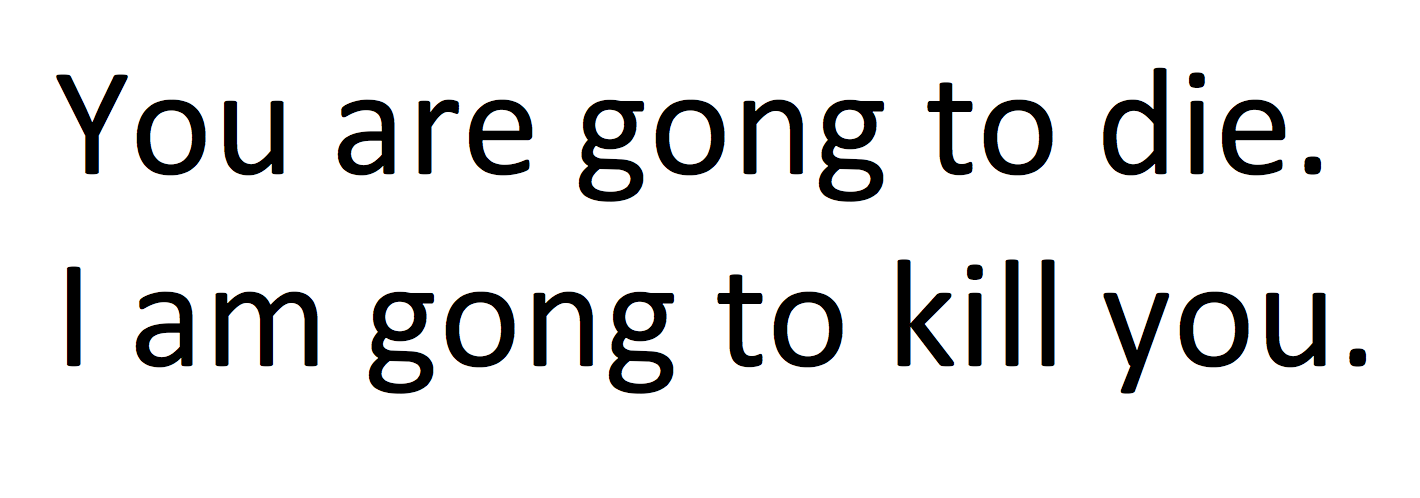

In the wake of the most recent mass school shooting, the solution from the president and the NRA is a rehashing of an old idea—the “let’s arm the teachers” concept. It’s sort of like a cross between the old west and the nun with the deadly yardstick, I suppose. In the case of the president and the NRA, I am a bit cynical—I’m 100% convinced that they have latched onto this idea as a means to avoid actually doing anything about the gun problem in this country. That said, I can understand the logic of people who hear that idea and think it’s worth a try. For them, people who have never set foot in a classroom as anything other than a student, it makes sense. If a teacher has a gun, that teacher can end the attack more quickly by shooting the attacker. They don’t understand the flaw in this plan. The flaw is the idea that shooters like the one in Florida, Columbine, Newtown, etc. are exceptions. We like to see these shooters after the fact, and say “oh look at all of those signs. We should have seen this coming.” The problem, however, is that the signs here weren’t all that rare. This was a teenager who had lost his father and then his mother, was expelled for fighting over bullying and/or issues with the opposite sex, and had an obsession with violence and weapons. To be clear, this teenager IS a monster—we know this because he killed 17 people. If we look at him BEFORE that act, however, he is not particularly rare or even uncommon. Schools, even the best schools, have MANY hard-luck cases: kids with difficult home lives, kids who have experienced tragedy, kids with emotional issues, and more. These are the kids who were in the classes most of us weren’t in back in high school. They were the kids who sat alone or with other kids like them. Most people, as students, don’t really see them. But they are there. They are kids like Jack. I taught Jack during my very first year as a high school teacher. I had absolutely no idea what I was doing. As any good teacher will tell you, we desperately want to go back and apologize to that first group of students who we taught. Even still, Jack stands out. I still remember every detail about that moment—the moment of my first major “issue” as a teacher. The bell rang, students started filing out of the room, and this one little 9th grader dropped a folded up piece of paper on my desk without uttering a word to me. I hadn’t been collecting anything that day, but I picked up the piece of paper, unfolded it, and read this: I had no idea how to handle this at first. This was a pretty good school. Jack was a poor student, but he seemed like a genuinely nice kid. What do you do when a student tells you that he intends to kill you? In this case, I brought the note to a mentor, who walked me down to the office with a serious look on his face and made me show it to the principal. I felt awful. I was worried this student would get expelled or arrested. He was suspended—for one day—and was back in class the next week. He apologized. His mother wrote me a nice note, expressing her horror that her child would ever write such a thing, and insisting that he was trying to joke around with me. He had fallen in with a group of bad influences, she said. Within a week, things went back to normal. He did not manage to pass my class that year, but he never tried to kill me, either. That was the only year I taught Jack, but I kept tabs on the kid. I asked him how he was doing in 10th grade the following year, and offered advice on how to approach Shakespeare. I asked him how his mother was doing, in that “I know some of the horrid details of your home life but I can’t reveal to you that I know these things” way. I don’t want to get too into specifics, as the point here is not to reveal Jack’s true name or identity, but let’s just say that there was plenty in this 15 year old’s background that could have been considered a “sign that we missed.” I lost track of Jack in 11th and 12th grade. The next time I saw him was at his own graduation. He was supposed to be lining up, but he was frantically looking around for the tie that he “misplaced.” I am reasonably certain that he never remembered to bring a tie, but he could not walk without one. I loosened the tie from around my own neck and tossed it to him. He lit up with a smile, made eye contact, and gave me the most authentic “thank you” I think I’ve ever heard. He then rushed off to line up for graduation. Other than a quick hand-off when he returned the tie, I have not seen Jack since. I went off to graduate school, and I lost track of this young man who had seen too many things in his life and who had once threatened to end mine. Why do I bring up Jack in this blog post? I don’t want to conflate him with the young man who did that horrible thing in Florida. Not at all. Nothing would make me happier than to hear that Jack is living a wonderful, happy, stable life right now. He deserves it. No, I bring up Jack because—until the young man in Florida decided to act on his threats—he could have been Jack. There are dozens of kids with horribly tragic circumstances in our schools. Only a handful turn out to be monsters. The rest? The rest are the special projects for teachers. They are the students we show up early for. They are the students who make the athletic teams even if they were on the bubble because we think they need the community the most. There is a phrase often associated with schools--in loco parentis—which literally means “in the place of the parent.” The phrase is usually used to indicate that teachers make decisions when the parents aren’t there. But what about the kids for whom the parents are absent altogether or might as well be? Teachers will always go that extra mile for a kid who has nobody else in their corner. It’s part of the nature of the profession.

It’s been a long time since I was in front of a high school classroom, but many of these kids stay with me: the kid who had no self-confidence and cried when she found out I called home for a positive reason; the kid who was on the path to being a massive bully before several teachers took him under their wings rather than giving up on him; the student who told me that his father beats him; the student whose parents sued the school system because he was gay and they wanted someone else to pay for his tuition at a school that could “make that go away.” These kids stay with me, even though I don’t really know what became of most of them. Every teacher has kids like this—kids with “warning signs” who we work a bit harder to help. What does this have to do with guns? Easy. No teacher—and it doesn’t matter how much training they have had or if they are former military—no teacher can aim a weapon at a student, even the toughest, most pain in the ass student that has ever graced their classroom, and pull a trigger. To point a gun at another person and pull the trigger, you have to be able to see that target as an enemy. To teachers, that isn’t “the enemy”—it’s our kid. Even in the best case scenario, there would be hesitation. Any teacher who claims to be able to do exactly that is either lying to themselves or should never be in front of a classroom or in possession of a gun. The only thing we can expect from adding guns to school buildings is a significant increase in accidental shootings. So what SHOULD we do? I am not particularly comfortable around guns. Especially guns designed for the mass slaughter of people. I don’t think that stricter background checks will catch ENOUGH people. Some folks will always slip through. If it were up to me, I would want all semi-automatic assault rifles banned. I understand that a lot of folks feel differently. How about this as a compromise. Let’s flip the script. Instead of running checks to look for (and all too often miss) reasons why people shouldn’t have a semi-automatic assault weapon, why don’t we have a multi-step process of affirmative checks—if someone wants to buy a semi-automatic assault weapon, they need to explain why they want/need one, demonstrating that they have trained, have a clean record, have a plan for safe storage, etc. It’s not as far as I would prefer when it comes to gun control while still leaving the option there for people who are able and willing to demonstrate that they have the need, training, and stability for such a weapon. As a solution, it isn’t perfect. But it’s a far sight better than putting a gun in my hand and asking me to end the life of one of my students. No teacher can do that. Even if a student did threaten to end my life, I could never fire a weapon at that student. I’d much rather lend him my tie.

In the interests of getting SOMETHING up on the blog, I figured I would bring out this theory I cooked up right after seeing Star Wars: The Force Awakens for the second time. I originally posted this on Buzzfeed Community, but with The Last Jedi only a few months away, I figured now was a good time to bring back my theory and see if I was right. Once I come back up for air in a few weeks, I will have a relative flurry of new posts on a range of things, including more theater reviews, a write up of my Cinematic Shakespeares class, a long overdue affirmation post, and a post about race and small town America that I’ve been working on for a while. Until then, let’s get our dweeb on with some Star Wars theories! After seeing Star Wars: The Force Awakens for the second time many months back, I began to notice a few details that might foreshadow a TOTAL shock moment in the next film (December’s upcoming Star Wars: The Last Jedi). Here’s my guess: Kylo Ren (aka: Ben Solo) is NOT in fact Han and Leia's son. He is Luke Skywalker's son. Wait, you say. That makes no sense. The film told us explicitly on several occasions that Kylo Ren was Han and Leia's son, right? Yes. It did. A New Hope also told us on several occasions that Darth Vader killed Luke's father and that Luke and Leia could be a romantic couple. The new trilogy is all about paying homage to the narrative structure of the original, and the original set up a LOT of misdirection in A New Hope in order to set up some epic reveals in Empire.  So why do I think Kylo Ren is really Luke's son? Let's start with the name "Ben." In the expanded universe, Luke and EU flame Mara Jade had a son named Ben (who, after being mentioned in SEVERAL of the novels, was finally born in Greg Keyes' Star Wars: The New Jedi Order, Edge of Victory II, Rebirth--the only thing longer than that child's gestation period was the title of the novel that depicted his birth). It made sense. Obi Wan Kenobi was a mentor to Luke. But why on earth would Han and Leia call their kid Ben? Leia never actually MET Kenobi, and Han only knew him for a few hours. They also BOTH knew him as "Obi Wan Kenobi." Only Luke knew him as Ben, and had the kind of relationship where he would name a child after him. So why would Han and Leia be raising Luke's child as their own? Because Jedi aren't supposed to get married or have kids. Luke can't walk away from his responsibility as a Jedi--not when he's the only one left. My argument is that he had the child, and asked his sister and best friend to raise it as their own so that he could fulfill his obligation AND be in the life of his child. It would be important for all involved to keep it mum, though. Connecting to this is the theory that Rey is Han and Leia's natural daughter. She is the epitome of her two parents merged together. I think she was at the Jedi academy when Ren wiped out the other students, and Luke chose to save her over the others, as a Sith must kill someone important to them to truly cross over to the dark side. This is part of the reason Vader was able to be redeemed. He THOUGHT he killed Padme, but he didn't. He also didn't kill Kenobi, who ended his own life (for just that reason, I believe). Thus, Luke sacrificed his other students in order to save his niece (and in a way, his son). He knew his niece would always be in danger if Ren knew about her survival or location, so he had to hide her.

Where did he hide her? A desert planet. With an old friend (remember the opening scene and the description of that character from the text scroll?) living just across the dune to keep an eye on her. And this old friend also happened to be the one who had the map segment that could lead to Luke… It's a mirror image of the way Kenobi stashed Luke on Tattoine. Luke himself couldn't fill the Obi-Wan role for two key reasons: he had massive guilt over sacrificing his other students to save his own family, and he had to hide Rey's presence/survival from both Ren AND Rey's parents (Han and Leia). The connection between Han/Leia and Rey is clear. Han IMMEDIATELY takes to Rey, as if she reminds him of someone he had lost. He even tells Leia about "the girl" immediately upon their reunion (the First Order is blowing up star systems, and Han's first order of business is to tell Leia about a junk scrounger he met along the way?). Add to that the scene between Han and Maz where she JUST finishes describing how she can recognize the eyes of people across generations, and then looks right at Han and says, knowingly, "Who's the girl?" AND she gives Rey the lightsaber. It looks at first like she reacts to the saber because it is described as belonging to Luke and his father before him. This leads us to think that she is Luke's daughter. But if she is Han and Leia's daughter, she STILL has the familial connection to the saber, as it once belonged to her grandfather. When Leia actually sees Rey for the first time, they share a real embrace (if it were one of mourning over Han, Leia would have been hugging Chewbacca, not this girl that knew her husband for about a day and a half). Leia, as a mother and as an adept of the force, IMMEDIATELY recognizes Rey as the daughter she thought dead. So even with all this--the fact that A New Hope included these kinds of misdirections, the little details that support the theory,etc--why would they do this in THIS movie? I think they are seeding the film with fake/less important mysteries (who are Rey's parents, who is Snoke, etc etc) to distract from this bigger mystery. The payoff, much like the original trilogy (again, the stated desire to pay homage to the originals) would come in the The Last Jedi. As Luke goes to confront Kylo Ren--the latter now thinking himself FULLY crossed over to the dark side--Luke insists that Kylo can still be saved. Kylo laughs in Luke's face, and delivers a line along the lines of "You think you can turn me? I KILLED my father!" To which Luke, looking sad, responds: "No, Ben. I am your father." And the theater explodes in roars of nerdgasm. I think this is how it has to work out in the next film. Search your feelings. You know it is true.

Wallbyrd is still kind of the newcomer to the Rochester theater scene. Virginia Monte’s emerging company has put on a few shows in recent years. If you saw The Winter’s Tale (MUCCC), The Duchess of Malfi (MUCCC), The Complete Works of William Shakespeare: Abridged, Romeo and Juliet (Highland Park Bowl), or The Importance of Being Earnest (Lyric Theater), then you’ve seen a Wallbyrd show. Wallbyrd productions tend to have several recognizable features. They like to do interesting things with light and stage effects, they like to re-imagine familiar concepts in new, unexpected ways, they put a priority on movement, and they go out of their way to make their shows accessible to a younger audience (this is not a “tights and ruffs” company). Their production of Macbeth is right in line with all of this. In Wallbyrd’s production, Scotland is a post-apocalyptic wasteland, filled with cannibal witches, warring tribes, and a mishmash of surviving aspects of culture. It is a world where someone who is 30 is old and 40+ is unrealistic, and it is a world where the ability to procreate is incredibly important. The post-apocalyptic Scotland is staged at the Lyric Theater, and utilizes a minimalist set, with few non-weapon props and a stage area filled with risers and platforms that could have easily been seen in a junkyard. Basically, picture a world that is one part Peter Pan and the lost boys and two parts Mad Max, and you’ll have a pretty decent idea of the world of this production. One of the things Wallbyrd has always done particularly well is approach classic texts in an off-center kind of way. They did this last summer in their production of Romeo and Juliet, where their Friar Laurence, usually played by a venerable old man, was played instead by Carl Del Buono as a “fresh from the monastery” friar who wanted to change the world. This change led to several heart-breaking moments, such as the one here when Laurence discovers Romeo’s dead body, realizes his role in the death, and can’t bear to look at the corpse of his young protégé: In Macbeth, there are several such moments, though two stood out to me more than most: the “banquet” scene and the funeral procession. In Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the title character throws a formal banquet, at which he sees the ghost of a man he’s just had murdered. It unnerves him, and he disrupts the mirth of the dinner party, giving the gathered nobles a first reason to start suspecting Macbeth’s role in the murder of the former king. It’s one of my favorite scenes in the play, primarily because there are so many different ways to do the scene. Does the audience see what Macbeth sees or do they see what the nobles see? It’s also a scene that lends itself to quite a bit of dramatic experimentation. The production at the Stratford Ontario Shakespeare Festival last year added a second ghost (Duncan, the murdered king) to further torment the title character. I was eagerly anticipating this scene in Wallbyrd’s production, and for the first time in ages, I didn’t see it coming. With little warning, the actors all stormed the stage in a highly choreographed dance number, complete with strobe lighting and a bit of mosh pit action. I initially had no idea what was going on. In fact, I turned to my neighbor to ask if we had fallen into an episode of In Living Color. Only when the ghost appeared did I realize that we were in the banquet scene, and once that connection was made, it made perfect sense. Wallbyrd loves to incorporate dance and contemporary music into their productions (as you can see from the attached clip of the Capulet Ball from last summer’s production of Romeo and Juliet), but this wasn’t superfluous in any way. A world with, effectively, no old people WOULDN’T have a formal, sit down banquet. What would a group of tribal teens and 20-somethings have as a social gathering? A rave, and that’s exactly what Wallbyrd gave us. The other scene that really stood out was more of an addition to the Shakespearean material than anything else. After Duncan is killed, a solemn funeral procession is performed. The scene opens with a priestess chanting a familiar tune (more on this below). The body of Duncan is brought in, and his signature battle axe is then handed to another priestess. A ceremonial passing of the torch of authority (in this case the “torch” being a pendant that is passed from Duncan’s corpse to Macbeth) follows. Finally, all of the cast files out through the audience, led by Duncan and his pall bearers. Two things impressed me about this scene. First, it is another example of Wallbyrd finding meaning between the lines. Second, it put the rock star cast on display. There were well over a dozen actors on stage for this scene. I don’t think any two actors were conveying the same emotion. Jonathan Lowery’s Lennox was stoic, with a set jaw. Eddie Coomber was beside himself with grief. Ged Owen’s Banquo was mourning, yet preoccupied, lost in his own thoughts. This was not a scene where everyone went out and just “acted sad.” Each actor—from star to unnamed extra—clearly had an idea as to how their character was specifically reacting to Duncan’s murder. This show rewards those who pay attention, as the characters along the margins are always doing something (I was particularly delighted by Jackson Mosher in the rave scene—he is desperately attempting to dance with a woman who has no interest whatsoever. It’s a minor play within a play, and these kinds of moments are scattered throughout the production). This, frankly, is another thing Wallbyrd seems to do well. They find amazing local actors. Many of the actors playing secondary and even bit parts have played leads in Rochester area productions. This trend goes in the other direction as well, as actors like Andy Head, who played the relatively minor part of Paris in last summer’s production of Romeo and Juliet, turned in a strong performance as Macbeth. I’m reminded of one of the arguments made by Bart Van Es in Shakespeare in Company, about how Shakespeare’s distinct style could be traced, in part, to the fact that he had an entire company of excellent actors to write for (an oddity at the time). This production featured several stand-out performances. Head’s Macbeth drove the action. The highlight moment, for me, came in what is Macbeth’s one big “Hamlet” speech (“Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow…”). It features one of the most quotable lines in the play: “It is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” Head began that line and then paused for a significant period of time before blurting out “by an idiot.” It was his character’s moment of realization—the first point since he actively decided to clutch the dagger and murder the king that he thought about what he had done and realized that none of it was worth it. Another stand out was Shawn Gray, who played Ross. Gray, who played a manic, almost childish Benvolio in last summer’s Romeo and Juliet was the consummate warrior in Macbeth. He played one third of the Macduff family unit—in this post-apocalyptic world, the family unit has been reimagined as collections of warriors and those who can still reproduce; Macduff (played by Caitlin Kenyon) is played as an infertile warrior woman who serves as the husband to Charlotte Moon’s pregnant Lady Macduff (with Gray’s Ross as the brother in arms, breeding male, and third member of the marital trio). In the text, Ross is a relatively minor character. In this production, Gray’s performance is impossible to ignore. While there were several other excellent performances, I would be remiss if I didn’t at least mention the tandem of murderers played by Eddie Coomber and Kiefer Schenk. These two local actors—who played the leads in Wallbyrd’s production of The Importance of Being Earnest earlier this year—simply belong on stage together. They are Beavis and Butt-head but with an absurd ability to simultaneously convey affect and nuance while they play such roles. Somewhere out there is a buddy cop movie with their names on it, and I’ll be the first in line to go see it. Many of the best moments of the play featured the young actress who played Banquo’s child, Fleance. Andy Head’s Macbeth and Fleance (played by Serene Selke-Fisher--thanks to Diana Louise Carter for the help with the name!) have a playful “uncle/niece” kind of relationship. One scene, before the murder of Duncan, shows Fleance trying to sneak up on her father—unsuccessfully. Moments later, Macbeth does succeed in sneaking up on Fleance and grabs her from behind. Macbeth, Banquo, and Fleance all clearly revel in this kind of game. Only a few scenes later, after the murder of Duncan, Banquo and Fleance prepare to leave on a short trip when Macbeth again grabs her from behind. Only this time, Banquo’s hand goes to the hilt of his sword. It is the first clear indication that he no longer trusts his once beloved comrade, and it adds to the trauma of later scenes in the play.

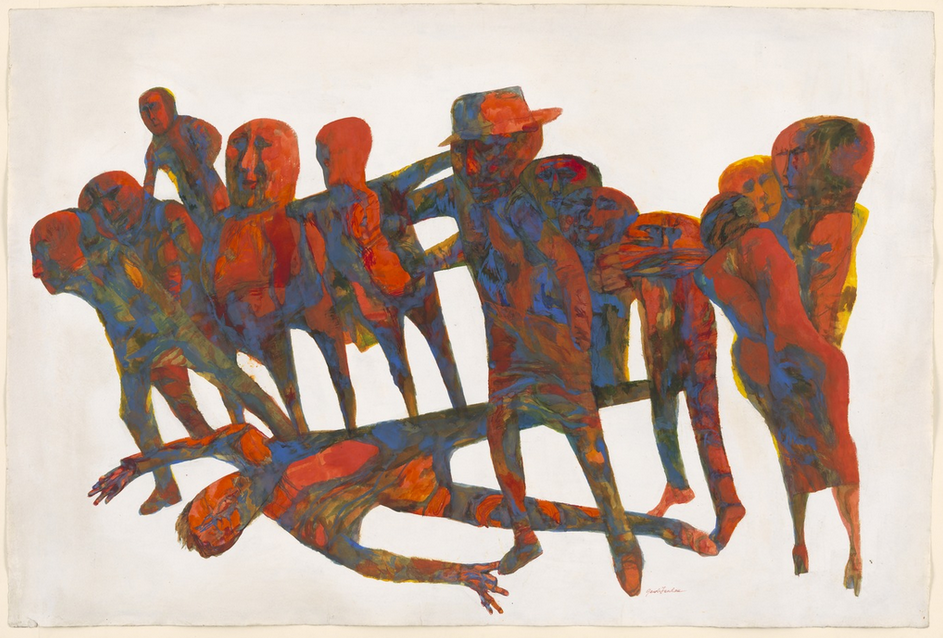

I also enjoyed the casting of a girl to play the role of Fleance—traditionally portrayed as Banquo’s son. The role is an important one, textually, because of the prophecy the witches speak that states that Banquo would not himself be a king, but he would sire a long line of kings. King James I, who ruled England during the second half of Shakespeare’s career, famously claimed to be a descendent of Banquo. As such, Fleance is a key character because even though Malcolm is king at the end of the play, we know that Fleance will, at some point, do great things (and pay attention to the final moments of this production—Fleance offers the audience a glimpse of things to come). On a side note, there are a couple of fun little “Easter egg” moments in this production, connected to J.R.R. Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings. The tune the priestess chants to begin Duncan’s funeral procession is the same tune as the “Mist and Shadow” song that Pippin sings in Return of the King, and several of the battle cries uttered by the cast as they (frequently) engage in battle are Dwarvish words (again from LotR). This is a fun tip of the hat by Wallbyrd to the idea that Tolkien wrote Lord of the Rings in part due to a dissatisfaction with the way Shakespeare cheated his way out of the prophecies in Macbeth (Tolkien had Ents marching and a woman kill the witch king, as opposed to Shakespeare having the army cut down bits of trees to hide their numbers and having Macduff born via Caesarian section). Although there is much to praise, there were some things that didn’t necessarily work in this production. The witches were a mixed bag. I loved the idea of a post-apocalyptic witches’ coven, particularly the idea that they would only be capable of speech when enough of them had gathered.* I also enjoyed the move to replace several servant characters with Hecate, played by the delightfully evil Alma Haddock. But the concept soon became overly complicated. In one scene, the witches have a choreographed, ballet-like dance number that feels entirely out of place in this post-apocalyptic world. There is another scene—the one where Macbeth returns to the coven to hear more prophecy—where puppets are utilized. It is a moment of prop-heavy action in what had been, to that point, a fairly barren stage. It might have been more effective to do the effects for the prophecies with light, as Wallbyrd has done so often in the past, or to have constructed more terrifying puppets. The movement in the puppet scenes was suitably eerie, but the puppets themselves, particularly the large one with a "monstrous" face just didn't convey terror. The scenes with the witches thus became some of the best and most flawed scenes in the play, because they had a phenomenal concept, but it felt like the concept was a little over-thought and possibly a bit too ambitious (regarding the puppet construction) for the time constraints of community theater. Another moment that concerned me was the level of violence in the murder of Macduff’s family. It is effective, and it is disturbing, and it is visceral. I completely understand the point of that scene and what it is supposed to do. It does, however, take this play to a very dark place—it is the darkest and most violent of any of the many productions of Macbeth I have seen—and I would be wary of bringing small children to see it (very “Red Wedding” for those of you who are Game of Thrones fans). A final concern/critique is one that the cast and crew of Wallbyrd couldn’t do anything about: the acoustics. The Lyric is a beautiful venue, and having a new venue for local theater is always a good thing. But it was a church in a past life, and the acoustics are designed to carry ONE voice through that domed roof. The odd part is that the echoing was worse when the acting was best—when actors changed pitch to convey emotion and nuance, the pitch changes created echoes. This was especially true of the scene where Ross reveals the fate of Macduff’s family (though Kenyon’s primal scream of anguish was powerful and believable) as well as the final battle between Macbeth and Macduff. Ultimately, this was a show I had long been looking forward to seeing. Virginia Monte’s concept for the show was everything that makes a Wallbyrd production worth seeing and her all-star cast of local talent took that concept and made it a reality. To be honest, this show doesn’t quite hit the same highs as last summer’s Romeo and Juliet--though it will likely be a while before anything does hit that mark; Wallbyrd's Romeo and Juliet set a standard for quality in Rochester community Shakespeare--but Macbeth felt like it had the potential to be even better with a little more time and some editing. That, in itself, is remarkable, and what they DID achieve is still an excellent show, and well worth seeing if you are in the Rochester area. Ticket info HERE. * Disclaimer—I was the dramaturge for this show. Virginia and I had several conversations about the links between Banquo and James I, as well as many coffee-fueled talks about the witches. I was basically the walking reference text in the early stages of the show’s conception, and was not involved in any of the rehearsals or world-building. As such, my review is based entirely on my experience watching the show for the first time. This will be a short one, as this is a post I hadn't planned on writing (I've been working on a more positive post for a bit, and I will likely add a post soon talking about the summer class I just finished teaching). As a Renaissance scholar, it's been impossible NOT to follow the story about the Public Theater's production of Julius Caesar. To be perfectly clear up front, this blog post is NOT going to re-hash all the points that have been made by others in my field. Yes, the rage from Republicans regarding this production is misplaced. This is a matter of fact, not one of opinion. Sarah Neville has shown how the play is, by design, not about sending a singular political message, but rather how it, through its "interpretive instability" leads people to see what they want in the text, appropriating it along those lines. Jyotsna G. Singh offers an historical context for the play, pointing out similarities between Caesar in Shakespeare's time and the political situation today. Singh notes that "Shakespeare had inherited over 1,600 years of ambiguity, with little consensus over whether Caesar's killing was justified." The result of such ambiguity was a play where heroes and villains are painted in tones of gray. Finally, Sophie Gilbert at The Atlantic has shown the absurdity of being outraged at the Public Theater's production due to the fact that it's not the first, second, or even third time such an angle has been taken with this play. A 2015 production put Hillary Clinton in the Caesar role. A 2012 production put Barack Obama in the Caesar role. Earlier productions featured JFK and Reagan. So I wasn't going to write about the Caesar outrage. It seemed that it had all been covered. But a combination of humidity induced insomnia and the fact that I am literally writing this from the scholar residence at the Folger Shakespeare Library has made me change my mind about joining the fray. There IS one aspect of this issue that I have yet to see anyone address (not saying it hasn't been, just saying I haven't seen it). Almost every character in this play exists on a razor's edge of morality. Caesar may have been a tyrant, and he may have been a savior. Antony, Lepidus, and Octavius may have been acting in the name of friendship, and they may have been acting in the name of self-interest. Each conspirator falls along the spectrum of morality in terms of their motive, and at the very least, you must admit that good men and bad men alike stab Caesar. In a play replete with such moral ambiguities, there is one scene that is clearly a depiction of immorality: the murder of Cinna the Poet. It's a short scene, and one that the education wing of the Folger Library uses frequently (another reason, perhaps, this scene came to mind tonight). You can see the scene HERE if you aren't familiar with it. This scene follows shortly after the famous "dueling speeches" scene where first Brutus gives a speech that gets the mob riled up in favor of the conspirators, and then Mark Antony gives a response that turns the Roman mob against the conspirators. By the time the two orators--both of whom seem to truly believe that they are acting in the best interests of Rome--are finished, the Roman mob is out of control. They don't trust anybody and, following the lead of their politicians, they are filled with suspicion, doubt, anger, and violence. That is their state when they encounter gentle Cinna the Poet, who unfortunately shares a name with a conspirator. The angry mob gangs up on Cinna, intimidates him, interrogates him, and finally kills him. Note the final lines of this scene, however. This is not a case of mistaken identity. Cinna the Poet does reveal that he is not one of the conspirators. That he is Cinna the Poet, not Cinna the Conspirator. The mob seemingly takes that information at face value. And then they kill him anyway, for his "bad verses."

The mob wasn't trying to achieve a goal. They did not believe in a particular ideology. Not really. They were enraged, that rage had to be vented, and it ultimately didn't matter who was on the receiving end. This, too, has been happening in our current politically charged theatrical situation. The Boston Globe ran a story this week reporting that Shakespeare theaters across the country, from Lenox, Mass. to Dallas, Texas and several more in between, have been receiving dozens of unhinged threats from people offended by the Public Theater's production. These theaters, which have nothing to do with the Public's production, received dozens of messages, "including threats of rape, death, and wishes that the theater's staff is 'sent to ISIS to be killed with real knives.'" These threats were fueled by the intentional fanning of those initial flames of rage. Long after it was clear that the play isn't about what people had been told, folks like Donald Trump Jr. tried to blame the production for the shooting in Virginia. Some of the actions were those of cowardice rather than those of opportunism. Delta and Bank of America, rather than standing firm and highlighting what the play is actually about, stepped aside and withdrew their support, lending the perception of credibility to a protest about nothing. But let's pause for a moment and ask an important question: What was the Roman mob actually angry about? Were they angry at the conspirators for killing Caesar? Were they angry at themselves for cheering Brutus after his speech? Did they feel deceived by Brutus? Does it have anything to do with Brutus, Antony, Caesar, or any of the rest? That's the question of this play, because anyone who has been paying attention lately can see that that's where we are right now. Mobs of people protest and counter protest. They dox people online and send death threats. And it doesn't matter if the person (or in this case the play) is ACTUALLY doing what they've been told it does. Someone from their "side" has pointed at it and declared it the enemy. And, just like the Cinna the Poet scene, the mob isn't even going after the right target. We aren't thinking. We are segregated into packs who follow blindly and attack whichever target is identified, regardless of the facts. We are the Roman mob, and we are killing Cinna the Poet by the thousands because we are all too willing to mindlessly vent rather than stop and think. We, as a society, needed the message that the Public Theater's production was putting forward. Those who came out in droves to protest this production (and sent death threats to many other companies simply because they turned up in a flawed Google search) need to take a moment to look inward and figure out why they are so very angry. It isn't because of this play. As so many others have pointed out, that logic doesn't stand. The play literally ISN'T doing what the mob has been told it does. Yet they protest it anyway. They kill Cinna the Poet regardless of whether or not that target makes any sense, and it has to stop. We need to figure out why we are ACTUALLY so damned angry and why we are so content to be a mob whose unfixed rage can be manipulated so easily by so few for such selfish reasons. Our elected leaders need to decide if this cut-throat game of win at all costs via violent rhetoric is worth the inevitable result. And remember that "inevitable result" is precisely what Julius Caesar is about. This play shows us what happens when society reaches such a point. Rome (the United States) falls into ruin and despotism. And while the dream of Rome survives elsewhere, Rome itself never truly recovers. It isn't a play about one side violently deposing the other. It's a play about the collapse of democratic society where everyone from every side loses. Think about that next time the occasion to "kill Cinna for his bad verses" presents itself. And then maybe see the play rather than wishing death upon others. After a total of five flights, including several tornadoes, one highway fire, a Midwestern hailstorm, and a faint earthquake, I have ventured to and returned from the 2017 Shakespeare Association of America conference in Atlanta, Georgia. I'm somehow simultaneously energized and completely exhausted, so I'm going to go full listicle on this entry. So here are my four big takeaways from SAA 2017 (or rather, one MASSIVE takeaway and three carry-on items): This was definitely one of the more interesting conference travel stories thus far in my career. In the week prior to SAA, one of Atlanta's major highways caught fire and collapsed. A few days before the start of the conference, tornadoes swept through the area. On the day before the conference, "travel day" if you will, the tornadoes returned and, for a time, the Atlanta airport was shut down completely. My own planned simple trip--Rochester to Baltimore to Atlanta--was supposed to be a quick jaunt down, putting me in Georgia at about 4pm. When I arrived in Baltimore, however, I quickly learned that my flight to Atlanta had been canceled. I was told that they could put me on a plane to Detroit, and catch a flight to Atlanta from there, assuming the airport re-opened in the interim. This was a gamble. I'm related to roughly 72% of the Baltimore/DC area. If I were to be stranded at BWI, there would be no shortage of beds and home cooked meals available to me. Detroit? I don't even know anyone out there. But my panel was the next morning, so I took the gamble and got on the plane. When we landed in Detroit, naturally it started hailing with massive flashes of lightning, one of which scared a flight attendant so much that she nearly fell out of her seat (not a great sign, I gather). Regardless, the airport in Atlanta had re-opened and we took off for the last leg of the trip. I arrived in Atlanta at about 10pm none the worse for wear, and the delays were made bearable by the non-stop Twitter posts about Shakenado, complete with choice lines from The Tempest and King Lear. There were MANY folks who were not as fortunate as I, and most of the panels were missing members. It's the kind of thing that, in most situations, would make people turn into pits of negativity, but not here. Everyone was laughing and optimistic. There were jokes that the dissertation prize should be awarded to the best travel story. One of the seminars I audited decided as a group to move their session to Saturday because a participant was en route from Abu Dhabi and they wanted to give that person the best chance of making the seminar. Another seminar I audited had four members participating via video chat. It's not like SAA was filled with negativity or anything last year (my first SAA), but the travel difficulties seemed to bring everyone together and put us all in the mood to embrace the absurd. On a side note, and I'm not entirely certain how this all began, there was a Furry convention in the hotel next to ours. As such, more than once, furries and Shakespeareans were interacting and engaging in jovial conversation. This was most evident on social media, where furries were explaining their culture to curious Shakespeareans while also expressing their appreciation for the SAA hashtag (my sense was that many of the furries had expected "Shakespeareans" to fit an old, stodgy, humorless image, and they seemed tickled that our humor trended more towards the fifth grade level at times). Andy Kesson blogged about it a bit--and had some great responses from the Furry community. SAA is one of the only conferences I know that utilizes the seminar format, and with my second SAA under my belt, I'm loving that format more and more. I attended three seminars this year: Cognition in the Early Modern Period (the one I participated in), Alternatives to the Term Paper, and A Digital Textbook for DH Shakespeare. I had initially planned to go to the seminar on John Marston--both because of my scholarly interest in Marston's Antonio plays and to say hello to Jason Gleckman, a scholar I met at my very first conference several years ago. Unfortunately, the Marston seminar was missing several people (including Jason Gleckman), and they decided to push it back to a later time slot. While I was trying to figure out which seminar to attend instead, I ended up in a short but productive conversation with James Bednarz, who suggested that I look at a recent book by John Kerrigan (Shakespeare's Binding Language) as I continue to revise my paper on Love's Labour's Lost. Being that this is only my second SAA, I don't have a huge frame of reference, but there seemed to be an enthusiastic interest in the pedagogical side of our field this year, which I found both refreshing and engaging. Two of the seminars that I audited were pedagogical in nature. After the official postponement of the Marston seminar, I found my way to the Alternatives to the Term Paper session. Participants in the seminar shared the various ways they were engaging students, including via performance, creative projects, editorial activities, and more. Some of the participants brought along examples of student work, and the seminar organizers invited the auditors to participate in the discussion and breakout sessions. Dana Aspinall, one of the official participants in the seminar, made several key points regarding the importance of thinking about what it is a term paper accomplishes and how to make sure that any substitute is of equal pedagogical merit/impact. The pedagogical theme continued into Friday, as I audited the workshop session whose participants were collaboratively constructing a web-based research and information tool for classroom use. It was an exciting session to attend, as the participants and organizers clearly began their project without a clearly pre-defined end product. Their work, both individually and collectively, was still taking shape and had the air of exploration about it. Whatever their work ultimately becomes, their early results were fascinating, and again it showed an interest on the part of SAA to take the lead on not just scholarly pursuits but pedagogical ones as well. One of the most brilliant and most terrifying things about SAA is the presence of an absurd number of people. From what I gather, SAA was expecting something in the neighborhood of 800+ people at this year's conference, and looking through the program, some of those people, speaking as a graduate student, can be terrifying. The big names are all at SAA. After citing these people for years, the idea of running into one at the hotel bar brings all the doubts of imposter syndrome rushing back. As a result, grad students tend to move through the venue surveying nametags--ninja style--so as to avoid any awkward situations with major scholars. The "name tag survey" is fraught with many potential perils. Not only is it awkward to scan the room at chest-height, but it's easy to get caught tag scanning and immediately over-think the result. If a scholar saw me scanning their tag and I kept going, is that scholar offended that I wasn't "looking" for them? The worst thing in the world is to say hello to a scholar as if both of us were real people, THEN catch sight of the name tag, and revert to this: Of course, that can't always be helped. I had a few such scenarios like that last year. Some involved one of my committee members (Jon Baldo) ushering me around the reception and introducing me to nametags that absolutely terrified me. Others involved promises. I work as a research assistant for Theodora Jankowski, and last year she instructed me to find Jean Howard and pass along her love. I just looked at Theodora and whined, "I can't just deliver love to Jean Howard! She's JEAN HOWARD!" Naturally, I DID see Jean Howard at the conference last year and did dig up the gumption to pass along Theodora's greeting. Of course that was the point where the woman standing NEXT to Jean Howard said "Oh do tell Theodora I said hello. My name is Phyllis Rackin." And then I died. That said, I am getting better at it. I saw Richard Preiss in passing this year and managed to tell him that I greatly enjoyed his book Clowning and Authorship in Early Modern Theatre. The two big events, the reception and the luncheon, are really the only time where everyone (or most everyone) seems to be in the same room, and if you are even mildly claustrophobic, it is easy to become overwhelmed in such a setting. It also makes the whole "name-tag scan" more difficult, as some have taken off these identifying markers and scanning whilst navigating a room full of hundreds of people (and many glasses of wine) can be disastrous. Last year the reception venue was also occupied in part by a massive bust of the man himself--William Shakespeare (based on the size, I half expected Edward de Vere, Christopher Marlowe, and Francis Bacon to burst out of it with an authorship-themed burlesque number). I did a bit better with the reception this year, after getting a bit overwhelmed by the number of people last year. For the second year in a row, however, I missed the luncheon. Last year, it was due to still being frazzled from the previous evening's reception. This year, it was because I had misplaced my ticket, and by the time I found it, I would have had to enter late (which put images of a Grad Student version of the prom scene in Carrie in my head--my head is a strange place at times). For a conference so massive, I think one of the more interesting takeaways this year is about the smaller connections. Last year, I tended to gravitate more towards people I already knew. People from my program, people from the year-long Folger seminar I did a while back, and people from previous professional experiences. This year, I ended up in three meaningful conversations with people whom I had never met before SAA 2017. Peter Hadorn, one of the other participants in my seminar, was one of these people, and we had a wonderful chat afterwards about his work on the Sonnets. I also had a couple of wonderful conversations with Dana Aspinall. My initial introduction was a little awkward. I wanted to tell him that I greatly enjoyed something that he had written, though for the life of me, I couldn't remember what that was--I just know that I have cited him several times. Dana received the compliment graciously, and indicated that it was probably his work on Taming of the Shrew, as that's what gets cited the most. When I next went up to my hotel room, I searched my computer and found that it was actually something he had written about Robert Armin and Will Kemp, and he seemed delighted when I saw him later and told him I had solved the mystery. This was one of those situations where a graduate student meets a senior scholar and walks away just as impressed with the person as with the work. Shortly before I left for the airport, I had a pre-arranged coffee chat with Kennesaw State's Keith Botelho. I had reached out to Keith on the advice of a former roommate (and Kennesaw graduate) Daniel Singleton. Daniel told me to keep an eye out for Keith last year, and when I didn't see him amidst the sea of Shakespeare, Daniel got more persistent this year, sending his e-mail, offering to make the digital introduction, and so on. Keith and I arranged to meet during Saturday morning's coffee break, and the first part of the conversation was almost eerie. He was prone to saying things that I had heard before, and it was at that point that I realized that I had heard them from Daniel. Clearly this professor had an impact on my former roommate. As the conversation progressed, it got easier and more casual. We joked about how Daniel really needed to propose to his girlfriend already, and the conversation then turned towards work. I am teaching a course this summer on cinematic Shakespeare--a course Keith has also taught. We spent a while discussing the pragmatic details (structure, course text, etc) and then geeked out a bit talking about various versions of Shakespeare that we'd seen. Finally, Keith shifted towards offering some job market advice, particularly about how and when to emphasize my experience teaching high school (I've heard from several sources that this kind of experience can be seen as a bad thing, but that's a topic for a whole other blog post, haha). I'm not sure if it was due to the storm, there being slightly fewer people from last year's SAA, me being a bit more comfortable, or some combination of the above, but these kinds of individual, meaningful conversations just seemed easier to come by this year. I flew out of Atlanta professionally connected to three scholars at three different institutions who I hadn't known at all prior to going there. And those connections felt authentic (ie- not like some kind of forced "networking" game). This all brings me to my fourth major SAA takeaway, and it's the one that, if not for the intercession of a friend over sushi, I might have missed altogether. This plenary, which took place Friday morning (well, morning for me), was not initially on my list of sessions to attend. Friday was going to be a "sleep in and recover from the crazy travel" day, and I had planned to start my day with the luncheon. I had scanned the program, and saw the titles of the talks for this plenary. They didn't jump out at me as the sort of work that I did. I always try to be aware of race, and incorporate the topic into classroom discussion frequently, but for me to get up "early," said my subconscious mind, it had to be a topic that was "in my academic wheelhouse." It had to be the kind of work that I did. And then all of that changed because of sushi. For the second year running (officially a tradition?), Sam Dressel, Sydnee Wagner, and I went out for sushi at SAA. We found a great place and re-connected on Thursday night. As the meal wound down, Sydnee made a point of telling us that she really wanted us to go to the Color of Membership Plenary the next morning. She noted that, in large part, the plenary topic was intended for white scholars, and she was discouraged by how often the audience for race related panels is disproportionately filled with PoC. [UPDATE FOR CLARITY: To be clear, Sydnee loves seeing PoC there as well. Her discouragement at the relative dearth of white scholars seemed to be similar to the sentiment expressed by Dr. Little at the start of his talk. :) ] I told her I would definitely make an effort. The next morning, I officially decided to go. I still didn't think it was a topic that connected to the kind of work I did. But I wanted to go to support and show solidarity for Sydnee. Best. Decision. Ever. The plenary, which was recorded and can be viewed above, featured five speakers (or occasionally surrogates, as some folks were stranded by weather). Dennis Austin Britton opened with his discussion of a piece by Nikki Giovanni and what it means to "count" as a Shakespearean. Arthur L. Little Jr. followed up with the emotional high point of the panel, discussing the ways in which we, as a profession, diminish non-white narrative. Jean Howard offered a piece on being more aware of our scholarly white privilege, and Jyotsna Singh discussed the differences in representation on stage and in academia. Joyce G. MacDonald discussed issues of representation, or the lack thereof, particularly in locales such as her native Kentucky. These short descriptions do not do the plenary justice. Go back up to the video and listen to the speakers (though as an audio recording, you will miss out on Arthur Little's amazing blazer. In a smattering of minutes, that jacket had a bigger Twitter following than I do, haha). Seriously. Go watch it. I'll wait. Here are some of the Twitter real-time reactions to help put you in the moment: Back? Good! I want to bring my focus specifically to the papers from Little and MacDonald. Little discussed issues of visibility and the control of identity. He relayed narrative examples--such as the time he was told by his first Shakespeare professor that that professor "wasn't impressed" with him and the time he was told that there wasn't enough room in the faculty display for a book he had published. He openly wondered whether or how to take such encounters. Essentially, should he take such encounters "personally"? Little's talk opened with a comment that he over-heard from two middle-aged white male scholars who had decided not to go to the plenary because "I'm not very interested in that stuff." I'm not middle-aged, but it felt like he could have been talking about/to me. I am interested in issues of race, but as Little's impassioned talk progressed, I began to wonder why that "interest" didn't translate into something that I do. Why does affect not translate into action?