|

Just a quick post to let y'all know that I was on Connections with Evan Dawson on NPR this afternoon. Evan had myself (in my role as a dramaturge), WallByrd artistic director Virginia Monte, and performer/scholar Jamie Tyrrell on the show to chat about issues related to putting on plays like The Taming of the Shrew in the era of the #MeToo movement. Jamie, Virginia, and I started the conversation 20 minutes before even going up to the studio, and continued the conversation long after the show had ended (I think the ladies at the front desk of WXXI thought we had moved into the lobby permanently, haha). See below for a link to listen to the show, if you are so inclined, and a couple of photos from the visit! Now back to the dissertation revision! Be good! Link to the show: HERE

Or go to the web address directly: http://wxxinews.org/post/connections-reexamining-taming-shrew-era-metoo

3 Comments

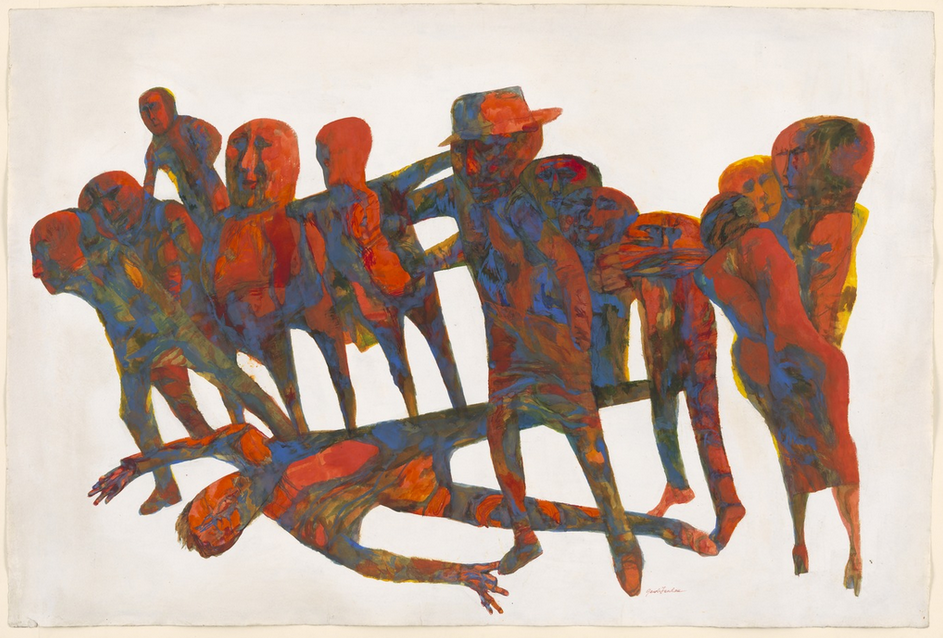

This will be a short one, as this is a post I hadn't planned on writing (I've been working on a more positive post for a bit, and I will likely add a post soon talking about the summer class I just finished teaching). As a Renaissance scholar, it's been impossible NOT to follow the story about the Public Theater's production of Julius Caesar. To be perfectly clear up front, this blog post is NOT going to re-hash all the points that have been made by others in my field. Yes, the rage from Republicans regarding this production is misplaced. This is a matter of fact, not one of opinion. Sarah Neville has shown how the play is, by design, not about sending a singular political message, but rather how it, through its "interpretive instability" leads people to see what they want in the text, appropriating it along those lines. Jyotsna G. Singh offers an historical context for the play, pointing out similarities between Caesar in Shakespeare's time and the political situation today. Singh notes that "Shakespeare had inherited over 1,600 years of ambiguity, with little consensus over whether Caesar's killing was justified." The result of such ambiguity was a play where heroes and villains are painted in tones of gray. Finally, Sophie Gilbert at The Atlantic has shown the absurdity of being outraged at the Public Theater's production due to the fact that it's not the first, second, or even third time such an angle has been taken with this play. A 2015 production put Hillary Clinton in the Caesar role. A 2012 production put Barack Obama in the Caesar role. Earlier productions featured JFK and Reagan. So I wasn't going to write about the Caesar outrage. It seemed that it had all been covered. But a combination of humidity induced insomnia and the fact that I am literally writing this from the scholar residence at the Folger Shakespeare Library has made me change my mind about joining the fray. There IS one aspect of this issue that I have yet to see anyone address (not saying it hasn't been, just saying I haven't seen it). Almost every character in this play exists on a razor's edge of morality. Caesar may have been a tyrant, and he may have been a savior. Antony, Lepidus, and Octavius may have been acting in the name of friendship, and they may have been acting in the name of self-interest. Each conspirator falls along the spectrum of morality in terms of their motive, and at the very least, you must admit that good men and bad men alike stab Caesar. In a play replete with such moral ambiguities, there is one scene that is clearly a depiction of immorality: the murder of Cinna the Poet. It's a short scene, and one that the education wing of the Folger Library uses frequently (another reason, perhaps, this scene came to mind tonight). You can see the scene HERE if you aren't familiar with it. This scene follows shortly after the famous "dueling speeches" scene where first Brutus gives a speech that gets the mob riled up in favor of the conspirators, and then Mark Antony gives a response that turns the Roman mob against the conspirators. By the time the two orators--both of whom seem to truly believe that they are acting in the best interests of Rome--are finished, the Roman mob is out of control. They don't trust anybody and, following the lead of their politicians, they are filled with suspicion, doubt, anger, and violence. That is their state when they encounter gentle Cinna the Poet, who unfortunately shares a name with a conspirator. The angry mob gangs up on Cinna, intimidates him, interrogates him, and finally kills him. Note the final lines of this scene, however. This is not a case of mistaken identity. Cinna the Poet does reveal that he is not one of the conspirators. That he is Cinna the Poet, not Cinna the Conspirator. The mob seemingly takes that information at face value. And then they kill him anyway, for his "bad verses."

The mob wasn't trying to achieve a goal. They did not believe in a particular ideology. Not really. They were enraged, that rage had to be vented, and it ultimately didn't matter who was on the receiving end. This, too, has been happening in our current politically charged theatrical situation. The Boston Globe ran a story this week reporting that Shakespeare theaters across the country, from Lenox, Mass. to Dallas, Texas and several more in between, have been receiving dozens of unhinged threats from people offended by the Public Theater's production. These theaters, which have nothing to do with the Public's production, received dozens of messages, "including threats of rape, death, and wishes that the theater's staff is 'sent to ISIS to be killed with real knives.'" These threats were fueled by the intentional fanning of those initial flames of rage. Long after it was clear that the play isn't about what people had been told, folks like Donald Trump Jr. tried to blame the production for the shooting in Virginia. Some of the actions were those of cowardice rather than those of opportunism. Delta and Bank of America, rather than standing firm and highlighting what the play is actually about, stepped aside and withdrew their support, lending the perception of credibility to a protest about nothing. But let's pause for a moment and ask an important question: What was the Roman mob actually angry about? Were they angry at the conspirators for killing Caesar? Were they angry at themselves for cheering Brutus after his speech? Did they feel deceived by Brutus? Does it have anything to do with Brutus, Antony, Caesar, or any of the rest? That's the question of this play, because anyone who has been paying attention lately can see that that's where we are right now. Mobs of people protest and counter protest. They dox people online and send death threats. And it doesn't matter if the person (or in this case the play) is ACTUALLY doing what they've been told it does. Someone from their "side" has pointed at it and declared it the enemy. And, just like the Cinna the Poet scene, the mob isn't even going after the right target. We aren't thinking. We are segregated into packs who follow blindly and attack whichever target is identified, regardless of the facts. We are the Roman mob, and we are killing Cinna the Poet by the thousands because we are all too willing to mindlessly vent rather than stop and think. We, as a society, needed the message that the Public Theater's production was putting forward. Those who came out in droves to protest this production (and sent death threats to many other companies simply because they turned up in a flawed Google search) need to take a moment to look inward and figure out why they are so very angry. It isn't because of this play. As so many others have pointed out, that logic doesn't stand. The play literally ISN'T doing what the mob has been told it does. Yet they protest it anyway. They kill Cinna the Poet regardless of whether or not that target makes any sense, and it has to stop. We need to figure out why we are ACTUALLY so damned angry and why we are so content to be a mob whose unfixed rage can be manipulated so easily by so few for such selfish reasons. Our elected leaders need to decide if this cut-throat game of win at all costs via violent rhetoric is worth the inevitable result. And remember that "inevitable result" is precisely what Julius Caesar is about. This play shows us what happens when society reaches such a point. Rome (the United States) falls into ruin and despotism. And while the dream of Rome survives elsewhere, Rome itself never truly recovers. It isn't a play about one side violently deposing the other. It's a play about the collapse of democratic society where everyone from every side loses. Think about that next time the occasion to "kill Cinna for his bad verses" presents itself. And then maybe see the play rather than wishing death upon others. Gawain and the Trauma of Romance AKA: Branagh and Olivier Walk into a Bar & Split a Henry Fifth1/7/2017 I want to rewind a little bit this week, and talk about something from last month. On December 13th (the last day of the semester at the University of Rochester), the Rossell Hope Robbins Library (i.e.: the non-circulating medieval library on campus where I work a few hours each week) put on a dramatic reading of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. It was a risk. Even though food was promised in the poster, trying to pull off anything at the end of a semester is hit or miss. Our new-ish director at the Robbins Library, Marie Turner, cooked up the idea, and brought in a rock-star group of medievalists and hangers-on to perform sections. Russell Peck, Steve Rozenski, and Sara Higley all wowed the full audience with their lyrical delivery of Middle English passages. Thom Hahn, having been assigned a modernized section, tried to join the Middle English fun by bringing along his own copy of the text. Several grad students (including myself and first year Rose Zaloom) helped out as well, and the pieces were all stitched together via narration by the incomparable Alan Lupack.  My section was a narrative bit from the Third Fitt, mostly involving the hunt for Reynard the Fox. I played up the suggestive sexual humor in the scenes between Gawain and Lady Bertilak. After the show, Marie came up and said that she was pleased with how it all went, and that she was hoping that I would spice up my section with a bit of humor (to which Alan Lupack responded, "Oh, so you needed a ham and went to Scott? Good call." Oh Alan. He knows me so well). The section that I read featured a bit of the Romance and a bit of the Realistic. And I couldn't help but spend several days thinking about the incredibly odd structure of Gawain. I've always been fascinated by Gawain and the Green Knight. It's such a perfect balance of the magical perfection of medieval Romance and the grim reality of more modern genres. I think that's why it's so hard to stage/film without venturing towards the ridiculous (Sean Connery, I'm looking at you and your sparkly green chest hair on this one). As a text, it's generically muddy, and that very muddiness has been one of the things I've loved about Gawain. W.R.J. Barron ("Arthurian Romance: Traces of an English Tradition," English Studies 61.1 (1980): 2-23) noted the ambiguous line between the real and the fantastic in Gawain as an indicative feature, arguing that "subtly controlled, realism can be an aid to perspective--as in Gawain's journey out of legendary Logres into the concrete geography of North Wales and back into the Never Never Land of Romance beyond the Wirral" (Barron 18). And it really is a journey from magic to reality and back again. Gawain is the Romance knight in Camelot, but his journey to Chapel Green is detailed, painful, and arduous. Gawain on several occasions comes close to death just getting to Chapel Green. He goes through things that one doesn't usually expect a Romance character to go through. In a way, Gawain almost engages in an inverted dream vision allegory, traveling from a fantastic world to a more visceral one and back again, learning a spiritual/moral lesson along the way. After our performance at Robbins (which was aided by a full house and some absolutely delicious Lebanese food), I kept turning these ideas over in my head, and I couldn't help but think that this generic confusion, this conflation of both the positive and the negative, the real and the magical, is what makes Gawain so special. It seems as if, particularly today, our entertainments are either dark and gritty or artificial and whimsical. Just look at two recent and popular television programs depicting pseudo-medieval worlds: Galavant and Game of Thrones. The former is clean, funny, and full of people with nary a hair out of place. Racial and gender equality is portrayed with a smile and a song, regardless of how anachronistic it may be (a point they make light about). The latter is dark and gritty. It is teeming with death, disease, deformity, and betrayal. Characters who trust and love tend to be the characters that die the soonest and in the most grotesque fashion. I know those two examples are a bit random and could easily be cherry picked. So lets pull something from my own wheelhouse: Shakespeare's Henry V. Textually speaking, this play is just as generically confused as Gawain. There are several tragicomic elements throughout, and the wooing scene at the end has been described by Donald Hedrick as "violence to genre." There are, however, two productions of this play that universally get mentioned: Olivier's and Branagh's. Olivier's production, filmed in the midst of a World War and striving to inspire a war-weary English population, showed a Romance Henry. He was clean, morally and wardrobally (that is officially now a word). After Agincourt, a spotless Olivier credits God, forgives an adoring Montjoy, and proceeds to an adoring populace. Branagh's production, responding to a century of morally complicated wars, was anything but clean. After Agincourt, Branagh, caked in blood and earth, carries the murdered boy (who would still somehow grow up to become Batman) from the field of battle amidst an array of corpses. Whatever Romance might be seen in Branagh is depicted as deviousness and manipulation. These two productions illustrate the thoughts I was having after our reading of Gawain. Too often, our texts are EITHER Romance or Gritty Realism. This is what makes Gawain special to me. I've always been particularly moved by the ending. Gawain, through much trial, returns to Camelot and tells the honest tale of what happened to him against Bertilak. He is not telling a heroic story. He is confessing his own shame, and displaying the badge of that shame. This was the response of his fellow knights: "Then the king comforted the knight, and the court laughed loudly at the tale, and all made accord that the lords and the ladies who belonged to the Round Table, each hero among them, should wear bound about him a baldric of bright green for the sake of Sir Gawain. And to this was agreed all the honour of the Round Table, and he who ware it was honoured the more thereafter, as it is testified in the best book of romance." They don't get it. Gawain's Round Table brethren don the green to mitigate Gawain's unique shame and announce their own honor. In my head, I always picture Gawain here in a similar situation to Isabella at the end of Measure for Measure--a character who seems stuck in a world with people who just don't get it. Trauma happened. Gawain has been changed at the core of his being. Having journeyed to the "real world" and seen his own imperfections, he can't go back to living normally in a Romance. Robert Margeson ("Structure and Meaning in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight," Papers on Language & Literature 13.1 (1977): 16-24) described this change in the character, arguing that "perfection, once lost, can by definition never be regained. For him the circle is broken, and his quest has been a linear movement into an as yet unknown world of fallibility and remorse" (18-19). This is why I like the idea of generically muddy texts. Trauma is real, and it changes people in ways that prevent them from simply returning to the world as they knew it before the traumatic event. By overemphasizing texts that drown in a world of trauma (Game of Thrones which, to be clear, I still love, although I get angry every time they kill a direwolf) or texts where trauma doesn't exist (Galavant, again, I still enjoyed it. Is it awful that I kind of want to see Galavant in Westeros and Ramsey Snow in Galavant's world?), we miss out on the opportunity to see characters heal. Art reflects the human experience. Gawain, defined at the outset by his membership in a brotherhood, realizes that he can only heal from his trauma independently. There are some texts lately that have been doing this well. Dennis Hopeless and Kev Walker created a pair of comic book mini-series back in 2013/14 called Avengers Arena and Avengers Undercover. The former involved a group of teenage heroes forced to fight each other in a death match (I know, I know. I really expected to hate it, but it ended up being fantastic. Check it out). Many of them died. Of the ones that remained, they had to live with the realization that they weren't the heroes they thought they were. Some of them killed. Some allowed others to kill for them. And the follow up series was all about the survivors coming to terms with that trauma. Going back to Henry V, I saw an amazing local production here in Rochester last year. Kate Sherman played Henry V, and her performance was a tight rope walk of trauma and performed strength. Sherman's Henry saw the horrors of war after Agincort. She recoiled from a defeated Montjoy who had not adoration, but clear hate in his eyes for the English monarch who had destroyed France. She struggled with the reality of the trauma that she saw all around her while balancing the necessity of maintaining a show of strength out of duty. Imagine a king with an awareness of Branagh's world and the realization that her people needed to see Olivier's moral simplicity. That's the Henry that Sherman delivered, and it was one of the more powerful productions of the play that I've seen. I could talk about these sorts of things all day and then some (Shakespeare, Gawain, comic books, Game of Thrones, and Galivant? I'm impressed I kept it as short as I did, haha). This is one of those posts where the point isn't overly clear even to me. I suppose that it came from a place where, due to current events, trauma is on my mind. Certain aspects of the world aren't quite like I had thought/hoped them to be. I keep waiting for some Galivant to pop into the picture, but Ramsey Snow keeps rearing his head. Trauma is real. Our art and drama does a fantastic job of depicting, producing and sensationalizing trauma. I guess my point with this post is just that I want to see more art/drama depicting characters recovering from trauma and re-adjusting. The world can never become what it was before. But it doesn't have to drown in the trauma. #BetheGawainYouWanttoSeeinThisWorld.

As a heads up, next week, I'm going to NYC to visit with some awesome cousins and some dear friends AND we're going to see the all-female cast production of the Tempest at St. Anne's Warehouse. I am beyond psyched. Be well. Scott |

Author

Welcome to the "Blue Collar Scholar" blog at TheRenaivalist.com (i.e. Scott O'Neil's personal and professional blog). Archives

April 2018

Categories

All

|

"Neque enim is verus est habendus orator, qui bene scit dicere, nisi et dicere audeat."

“No one who knows how to speak well can be considered a true orator unless he also dares to speak out.”

Lorenzo Valla, De falso credita et ementita Constantini donatione 1440

“No one who knows how to speak well can be considered a true orator unless he also dares to speak out.”

Lorenzo Valla, De falso credita et ementita Constantini donatione 1440

RSS Feed

RSS Feed