|

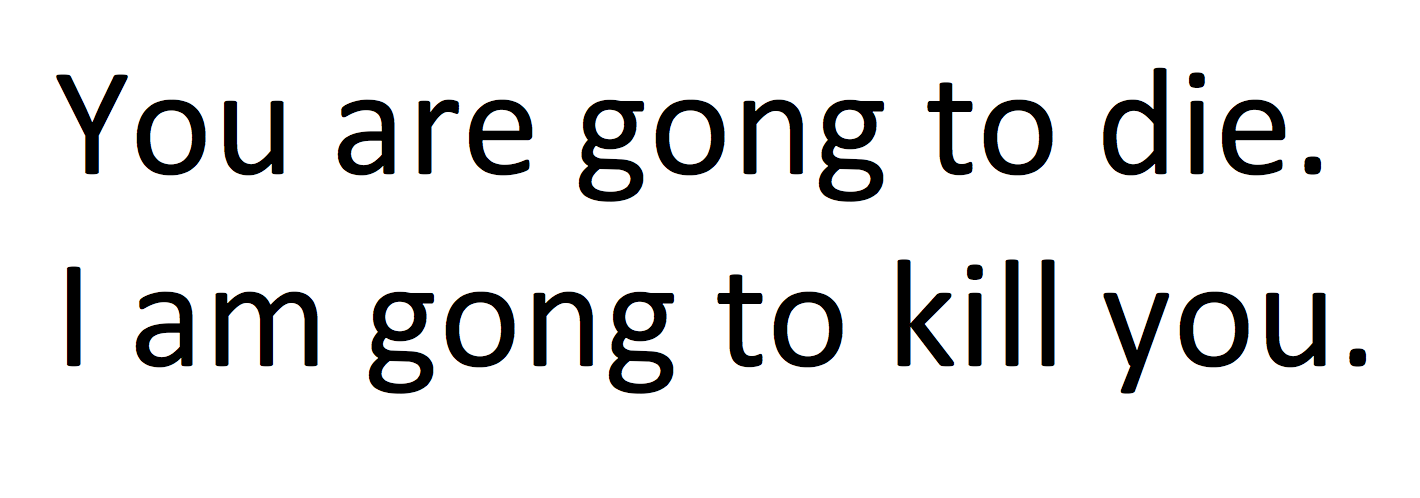

In the wake of the most recent mass school shooting, the solution from the president and the NRA is a rehashing of an old idea—the “let’s arm the teachers” concept. It’s sort of like a cross between the old west and the nun with the deadly yardstick, I suppose. In the case of the president and the NRA, I am a bit cynical—I’m 100% convinced that they have latched onto this idea as a means to avoid actually doing anything about the gun problem in this country. That said, I can understand the logic of people who hear that idea and think it’s worth a try. For them, people who have never set foot in a classroom as anything other than a student, it makes sense. If a teacher has a gun, that teacher can end the attack more quickly by shooting the attacker. They don’t understand the flaw in this plan. The flaw is the idea that shooters like the one in Florida, Columbine, Newtown, etc. are exceptions. We like to see these shooters after the fact, and say “oh look at all of those signs. We should have seen this coming.” The problem, however, is that the signs here weren’t all that rare. This was a teenager who had lost his father and then his mother, was expelled for fighting over bullying and/or issues with the opposite sex, and had an obsession with violence and weapons. To be clear, this teenager IS a monster—we know this because he killed 17 people. If we look at him BEFORE that act, however, he is not particularly rare or even uncommon. Schools, even the best schools, have MANY hard-luck cases: kids with difficult home lives, kids who have experienced tragedy, kids with emotional issues, and more. These are the kids who were in the classes most of us weren’t in back in high school. They were the kids who sat alone or with other kids like them. Most people, as students, don’t really see them. But they are there. They are kids like Jack. I taught Jack during my very first year as a high school teacher. I had absolutely no idea what I was doing. As any good teacher will tell you, we desperately want to go back and apologize to that first group of students who we taught. Even still, Jack stands out. I still remember every detail about that moment—the moment of my first major “issue” as a teacher. The bell rang, students started filing out of the room, and this one little 9th grader dropped a folded up piece of paper on my desk without uttering a word to me. I hadn’t been collecting anything that day, but I picked up the piece of paper, unfolded it, and read this: I had no idea how to handle this at first. This was a pretty good school. Jack was a poor student, but he seemed like a genuinely nice kid. What do you do when a student tells you that he intends to kill you? In this case, I brought the note to a mentor, who walked me down to the office with a serious look on his face and made me show it to the principal. I felt awful. I was worried this student would get expelled or arrested. He was suspended—for one day—and was back in class the next week. He apologized. His mother wrote me a nice note, expressing her horror that her child would ever write such a thing, and insisting that he was trying to joke around with me. He had fallen in with a group of bad influences, she said. Within a week, things went back to normal. He did not manage to pass my class that year, but he never tried to kill me, either. That was the only year I taught Jack, but I kept tabs on the kid. I asked him how he was doing in 10th grade the following year, and offered advice on how to approach Shakespeare. I asked him how his mother was doing, in that “I know some of the horrid details of your home life but I can’t reveal to you that I know these things” way. I don’t want to get too into specifics, as the point here is not to reveal Jack’s true name or identity, but let’s just say that there was plenty in this 15 year old’s background that could have been considered a “sign that we missed.” I lost track of Jack in 11th and 12th grade. The next time I saw him was at his own graduation. He was supposed to be lining up, but he was frantically looking around for the tie that he “misplaced.” I am reasonably certain that he never remembered to bring a tie, but he could not walk without one. I loosened the tie from around my own neck and tossed it to him. He lit up with a smile, made eye contact, and gave me the most authentic “thank you” I think I’ve ever heard. He then rushed off to line up for graduation. Other than a quick hand-off when he returned the tie, I have not seen Jack since. I went off to graduate school, and I lost track of this young man who had seen too many things in his life and who had once threatened to end mine. Why do I bring up Jack in this blog post? I don’t want to conflate him with the young man who did that horrible thing in Florida. Not at all. Nothing would make me happier than to hear that Jack is living a wonderful, happy, stable life right now. He deserves it. No, I bring up Jack because—until the young man in Florida decided to act on his threats—he could have been Jack. There are dozens of kids with horribly tragic circumstances in our schools. Only a handful turn out to be monsters. The rest? The rest are the special projects for teachers. They are the students we show up early for. They are the students who make the athletic teams even if they were on the bubble because we think they need the community the most. There is a phrase often associated with schools--in loco parentis—which literally means “in the place of the parent.” The phrase is usually used to indicate that teachers make decisions when the parents aren’t there. But what about the kids for whom the parents are absent altogether or might as well be? Teachers will always go that extra mile for a kid who has nobody else in their corner. It’s part of the nature of the profession.

It’s been a long time since I was in front of a high school classroom, but many of these kids stay with me: the kid who had no self-confidence and cried when she found out I called home for a positive reason; the kid who was on the path to being a massive bully before several teachers took him under their wings rather than giving up on him; the student who told me that his father beats him; the student whose parents sued the school system because he was gay and they wanted someone else to pay for his tuition at a school that could “make that go away.” These kids stay with me, even though I don’t really know what became of most of them. Every teacher has kids like this—kids with “warning signs” who we work a bit harder to help. What does this have to do with guns? Easy. No teacher—and it doesn’t matter how much training they have had or if they are former military—no teacher can aim a weapon at a student, even the toughest, most pain in the ass student that has ever graced their classroom, and pull a trigger. To point a gun at another person and pull the trigger, you have to be able to see that target as an enemy. To teachers, that isn’t “the enemy”—it’s our kid. Even in the best case scenario, there would be hesitation. Any teacher who claims to be able to do exactly that is either lying to themselves or should never be in front of a classroom or in possession of a gun. The only thing we can expect from adding guns to school buildings is a significant increase in accidental shootings. So what SHOULD we do? I am not particularly comfortable around guns. Especially guns designed for the mass slaughter of people. I don’t think that stricter background checks will catch ENOUGH people. Some folks will always slip through. If it were up to me, I would want all semi-automatic assault rifles banned. I understand that a lot of folks feel differently. How about this as a compromise. Let’s flip the script. Instead of running checks to look for (and all too often miss) reasons why people shouldn’t have a semi-automatic assault weapon, why don’t we have a multi-step process of affirmative checks—if someone wants to buy a semi-automatic assault weapon, they need to explain why they want/need one, demonstrating that they have trained, have a clean record, have a plan for safe storage, etc. It’s not as far as I would prefer when it comes to gun control while still leaving the option there for people who are able and willing to demonstrate that they have the need, training, and stability for such a weapon. As a solution, it isn’t perfect. But it’s a far sight better than putting a gun in my hand and asking me to end the life of one of my students. No teacher can do that. Even if a student did threaten to end my life, I could never fire a weapon at that student. I’d much rather lend him my tie.

1 Comment

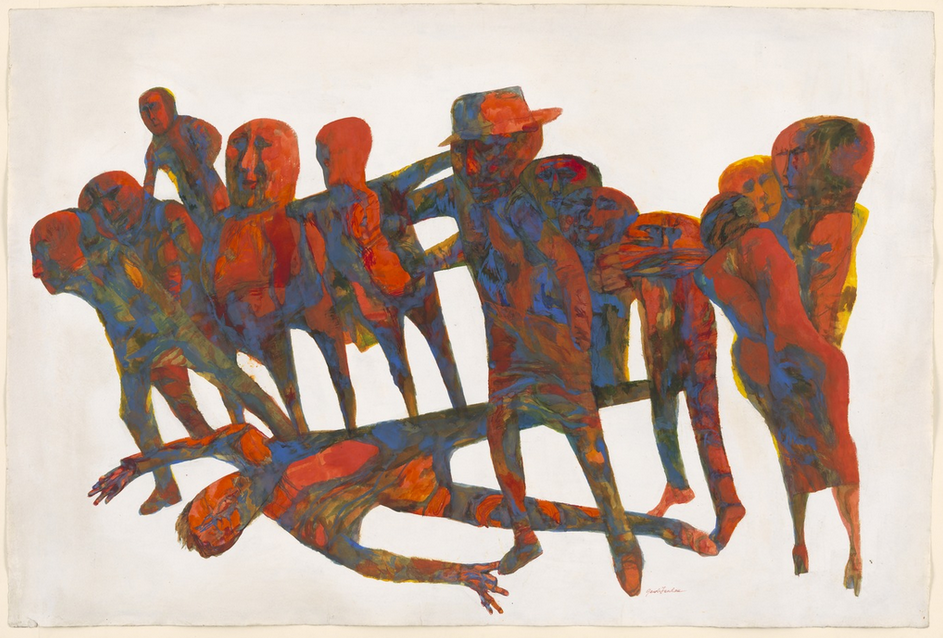

This will be a short one, as this is a post I hadn't planned on writing (I've been working on a more positive post for a bit, and I will likely add a post soon talking about the summer class I just finished teaching). As a Renaissance scholar, it's been impossible NOT to follow the story about the Public Theater's production of Julius Caesar. To be perfectly clear up front, this blog post is NOT going to re-hash all the points that have been made by others in my field. Yes, the rage from Republicans regarding this production is misplaced. This is a matter of fact, not one of opinion. Sarah Neville has shown how the play is, by design, not about sending a singular political message, but rather how it, through its "interpretive instability" leads people to see what they want in the text, appropriating it along those lines. Jyotsna G. Singh offers an historical context for the play, pointing out similarities between Caesar in Shakespeare's time and the political situation today. Singh notes that "Shakespeare had inherited over 1,600 years of ambiguity, with little consensus over whether Caesar's killing was justified." The result of such ambiguity was a play where heroes and villains are painted in tones of gray. Finally, Sophie Gilbert at The Atlantic has shown the absurdity of being outraged at the Public Theater's production due to the fact that it's not the first, second, or even third time such an angle has been taken with this play. A 2015 production put Hillary Clinton in the Caesar role. A 2012 production put Barack Obama in the Caesar role. Earlier productions featured JFK and Reagan. So I wasn't going to write about the Caesar outrage. It seemed that it had all been covered. But a combination of humidity induced insomnia and the fact that I am literally writing this from the scholar residence at the Folger Shakespeare Library has made me change my mind about joining the fray. There IS one aspect of this issue that I have yet to see anyone address (not saying it hasn't been, just saying I haven't seen it). Almost every character in this play exists on a razor's edge of morality. Caesar may have been a tyrant, and he may have been a savior. Antony, Lepidus, and Octavius may have been acting in the name of friendship, and they may have been acting in the name of self-interest. Each conspirator falls along the spectrum of morality in terms of their motive, and at the very least, you must admit that good men and bad men alike stab Caesar. In a play replete with such moral ambiguities, there is one scene that is clearly a depiction of immorality: the murder of Cinna the Poet. It's a short scene, and one that the education wing of the Folger Library uses frequently (another reason, perhaps, this scene came to mind tonight). You can see the scene HERE if you aren't familiar with it. This scene follows shortly after the famous "dueling speeches" scene where first Brutus gives a speech that gets the mob riled up in favor of the conspirators, and then Mark Antony gives a response that turns the Roman mob against the conspirators. By the time the two orators--both of whom seem to truly believe that they are acting in the best interests of Rome--are finished, the Roman mob is out of control. They don't trust anybody and, following the lead of their politicians, they are filled with suspicion, doubt, anger, and violence. That is their state when they encounter gentle Cinna the Poet, who unfortunately shares a name with a conspirator. The angry mob gangs up on Cinna, intimidates him, interrogates him, and finally kills him. Note the final lines of this scene, however. This is not a case of mistaken identity. Cinna the Poet does reveal that he is not one of the conspirators. That he is Cinna the Poet, not Cinna the Conspirator. The mob seemingly takes that information at face value. And then they kill him anyway, for his "bad verses."

The mob wasn't trying to achieve a goal. They did not believe in a particular ideology. Not really. They were enraged, that rage had to be vented, and it ultimately didn't matter who was on the receiving end. This, too, has been happening in our current politically charged theatrical situation. The Boston Globe ran a story this week reporting that Shakespeare theaters across the country, from Lenox, Mass. to Dallas, Texas and several more in between, have been receiving dozens of unhinged threats from people offended by the Public Theater's production. These theaters, which have nothing to do with the Public's production, received dozens of messages, "including threats of rape, death, and wishes that the theater's staff is 'sent to ISIS to be killed with real knives.'" These threats were fueled by the intentional fanning of those initial flames of rage. Long after it was clear that the play isn't about what people had been told, folks like Donald Trump Jr. tried to blame the production for the shooting in Virginia. Some of the actions were those of cowardice rather than those of opportunism. Delta and Bank of America, rather than standing firm and highlighting what the play is actually about, stepped aside and withdrew their support, lending the perception of credibility to a protest about nothing. But let's pause for a moment and ask an important question: What was the Roman mob actually angry about? Were they angry at the conspirators for killing Caesar? Were they angry at themselves for cheering Brutus after his speech? Did they feel deceived by Brutus? Does it have anything to do with Brutus, Antony, Caesar, or any of the rest? That's the question of this play, because anyone who has been paying attention lately can see that that's where we are right now. Mobs of people protest and counter protest. They dox people online and send death threats. And it doesn't matter if the person (or in this case the play) is ACTUALLY doing what they've been told it does. Someone from their "side" has pointed at it and declared it the enemy. And, just like the Cinna the Poet scene, the mob isn't even going after the right target. We aren't thinking. We are segregated into packs who follow blindly and attack whichever target is identified, regardless of the facts. We are the Roman mob, and we are killing Cinna the Poet by the thousands because we are all too willing to mindlessly vent rather than stop and think. We, as a society, needed the message that the Public Theater's production was putting forward. Those who came out in droves to protest this production (and sent death threats to many other companies simply because they turned up in a flawed Google search) need to take a moment to look inward and figure out why they are so very angry. It isn't because of this play. As so many others have pointed out, that logic doesn't stand. The play literally ISN'T doing what the mob has been told it does. Yet they protest it anyway. They kill Cinna the Poet regardless of whether or not that target makes any sense, and it has to stop. We need to figure out why we are ACTUALLY so damned angry and why we are so content to be a mob whose unfixed rage can be manipulated so easily by so few for such selfish reasons. Our elected leaders need to decide if this cut-throat game of win at all costs via violent rhetoric is worth the inevitable result. And remember that "inevitable result" is precisely what Julius Caesar is about. This play shows us what happens when society reaches such a point. Rome (the United States) falls into ruin and despotism. And while the dream of Rome survives elsewhere, Rome itself never truly recovers. It isn't a play about one side violently deposing the other. It's a play about the collapse of democratic society where everyone from every side loses. Think about that next time the occasion to "kill Cinna for his bad verses" presents itself. And then maybe see the play rather than wishing death upon others. |

Author

Welcome to the "Blue Collar Scholar" blog at TheRenaivalist.com (i.e. Scott O'Neil's personal and professional blog). Archives

April 2018

Categories

All

|

"Neque enim is verus est habendus orator, qui bene scit dicere, nisi et dicere audeat."

“No one who knows how to speak well can be considered a true orator unless he also dares to speak out.”

Lorenzo Valla, De falso credita et ementita Constantini donatione 1440

“No one who knows how to speak well can be considered a true orator unless he also dares to speak out.”

Lorenzo Valla, De falso credita et ementita Constantini donatione 1440

RSS Feed

RSS Feed