The Gunpowder Plot and King Lear

Your initial reactions/takeaways

Mysterious messenger/note

King's "intuition"

Discovery of gunpowder

Scramble to identify conspirators and craft the official narrative

Focus not on why, but on what if

Sermons

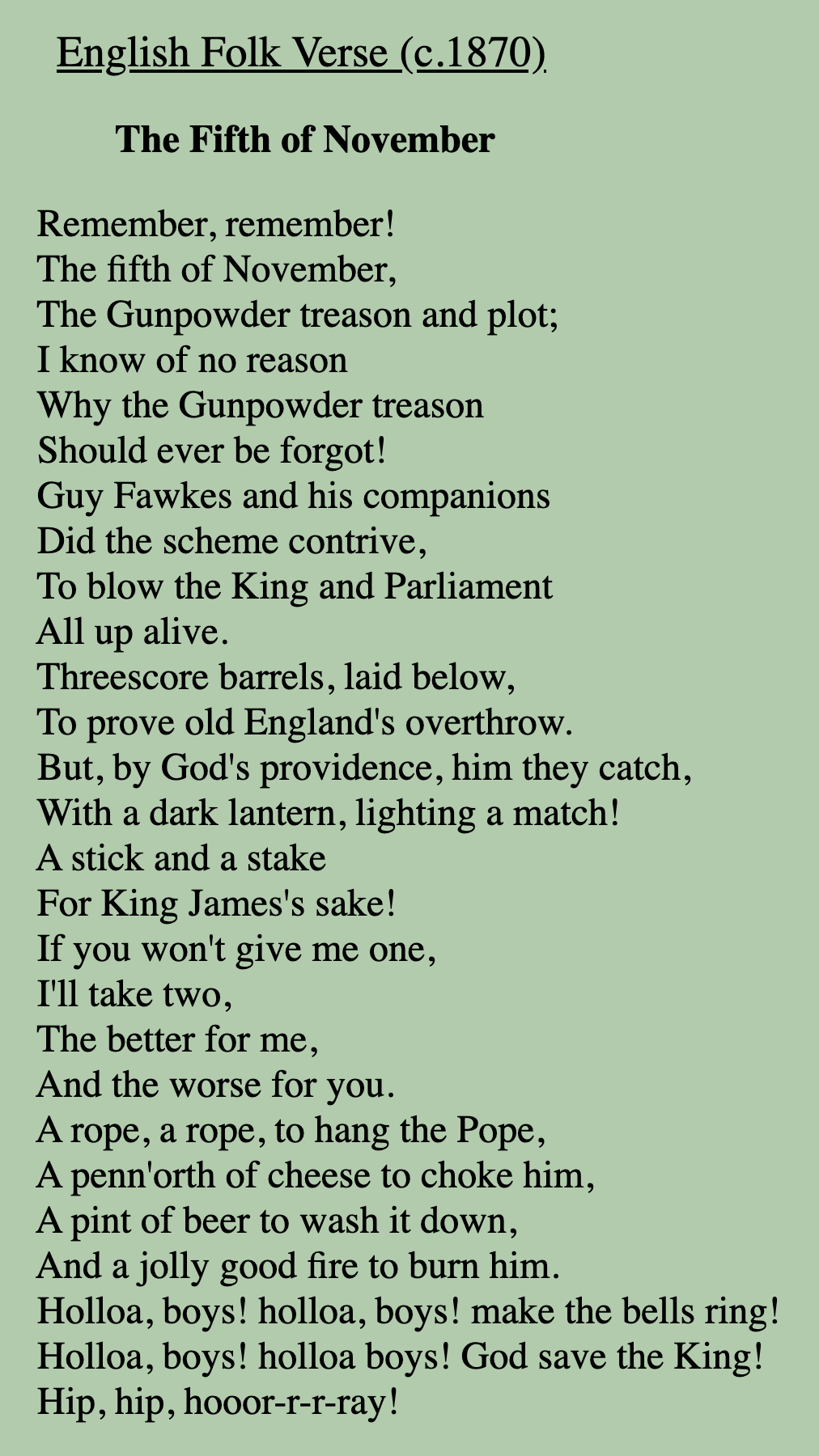

Art and performance

Princess Elizabeth

Catholic/Puritan coalition

Scramble to escape

Capture

Show trial

Executions

AITA:

BTW January and June: Lord Monteagle, “John Johnson” (AKA Guido “Guy” Fawkes), Robert Catesby, or Francis Tresham.

BTW July and December: Sir Everard Digby, Henry Garnet, or Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury.

Mysterious messenger/note

King's "intuition"

Discovery of gunpowder

Scramble to identify conspirators and craft the official narrative

Focus not on why, but on what if

Sermons

Art and performance

Princess Elizabeth

Catholic/Puritan coalition

Scramble to escape

Capture

Show trial

Executions

AITA:

BTW January and June: Lord Monteagle, “John Johnson” (AKA Guido “Guy” Fawkes), Robert Catesby, or Francis Tresham.

BTW July and December: Sir Everard Digby, Henry Garnet, or Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury.

LEGACY:

Gunpowder and Lear's Conclusion

Name a movie remake you know well.

Tell me what you know about King Lear.

As with so much of Shakespeare, the story of King Leir/Lear had been told several times before its appearance on the Globe stage. Geoffrey of Monmouth is credited with the earliest version, in his 12th century work, Historia regum Britanniae, a pseudo-historical text that constructed a continuous narrative between the legendary founder of Britain—Brutus, the grandson of the Trojan hero Aeneas—and, in effect, the Tudor/Stuart monarchs.[i] Monmouth’s version of Lear opens with the love contest, but none of Lear’s daughters are at that point married. After being spurned by his youngest child’s modesty, Lear proceeds to give only half of his kingdom to his elder daughters and their husbands, retaining the other half for himself until the time of his death (Geoffrey 82). Being impatient, his sons-in-law rebelled to secure the other half of the kingdom, deposing Lear (Geoffrey 83). With the help of his youngest daughter, Lear regains the throne and rules for another three years. At that point, Cordelia inherits the entirety of Britain, and rules peacefully for five years.

In many later versions of the story, this is where the plot ends, with Lear or Cordelia happily on the throne of a peaceful, united Britain. In Monmouth’s text, however, Cordelia’s nephews Marganus and Cunedagius, rebel against their aunt due to her being a woman ruler (Geoffrey 86). They imprison Cordelia, who “grieved more and more over the loss of her kingdom and eventually...killed herself” (Geoffrey 87). Her misogynistic nephews prove unable to share, however, and war against each other until Cunedagius kills his cousin and rules the whole of Britain peacefully for thirty-three years (Geoffrey 87).

The post-divestiture winnowing of Lear’s train was likely a borrowing from Raphael Holinshed’s version of the Lear story. Shakespeare almost certainly saw Holinshed’s version in the 1587 second edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles, which opens the story in much the same way as Monmouth: Lear engages in the love test, disowns his youngest child, marries off his elder daughters, and gives them each a quarter of the kingdom in dowry (Holinshed). Lear again reserves half the kingdom for himself while he lives, and his sons-in-law, Maglanus and Henninus, again rebel and seize Lear’s half for themselves. In Holinshed, however, we see Lear held by his sons-in-law, and “put to his portion, that is, to liue after a rate assigned to him for the maintenance of his estate, which in processe of time was diminished” by both of his would-be-heirs (Holinshed). Lear and Cordelia war against the usurpers, slaying Maglanus and Henninus, restoring Lear to the throne (Holinshed). The story continues from there as it had in Monmouth, with Cordelia ruling for five years after her father’s death before being deposed by her nephews and committing suicide in prison.

The version of the Lear narrative contained in Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (c. 1590) likely provided Shakespeare with the method of Cordelia’s death—hanging. Spenser’s version dispenses with Lear’s retention of half the kingdom and has him disown Cordelia, sharing his entire kingdom “twixt the other twain” (Spenser 166). Rather than the riotous knights in Shakespeare’s version, Spenser’s Lear sought to lead a private life in Albania (Scotland) with Gonoril (Spenser 166). Again, the elder daughters and their husbands scorn the former king, and again he goes to Cordelia who, through armed conflict, restores her father to the throne. Spenser’s addition to the post-script of the Lear narrative is the manner of Cordelia’s eventual suicide, as he is the first to indicate that “kept in prison long, / Till weary of that wretched life, her selfe she hong” (Spenser 167).

Oddly enough, the version that Shakespeare was most likely to have encountered—the anonymous King Leir--is the one least like his own.[ii] This version of the story features more blatantly villainous daughters—Regan hires a murderer to kill her father and his old friend Perillus after arranging to meet them in a thicket “some two miles from the court” (1.17.7-56).[iii] Even with more naked villainy than its predecessors, King Leir feels less threatening. There are comedic characters added to the plot, including disreputable sailors, a vice figure who is talked out of murder, and Mumford—a companion to the Gallian king—who seems almost obsessively focused on bedding any English woman. The play, as was common for Queen’s Men’s productions, was also clearly meant to serve as propaganda for Queen Elizabeth I. There are several scenes wherein the icons of her narrative of rulership are referenced to construct a thinly-veiled identification between Elizabeth and Cordelia. The French King calls Cordelia “Mirror of virtue. Phoenix of our age! / Too kind a daughter for an unkind father!” (1.16.46-47).[iv] With this connection between Cordelia and Elizabeth, it is no surprise that King Leir omits the part of the story wherein Cordelia is imprisoned by her nephews until her ultimate suicide. Instead, the play gives Leir the last speech, where he thanks all, culminating with the amorous Mumford who “lion-like” chased away Leir’s elder daughters and their husbands. The final words of the play are directed to Cordelia and the French King: “Come, son and daughter, who did me advance; / Repose with me awhile, and then for France” (1.29.175-176). Though the play—as per some of the earlier versions—suggests the possibility for tragedy, there is no element of tragedy represented in the conclusion at all. In King Leir, even the villains survive. This also marks the point where, Shakespeare’s text aside, retellings of the Lear story would begin going to great lengths to omit the detail of Cordelia’s delayed death.[v]

While Shakespeare sourced several elements of his Lear from earlier versions—the love contest and Cordelia’s imprisonment from Monmouth, the winnowing of the train from Holinshed, the hanging of Cordelia and Lear’s complete divestment from Spenser, and the humor from Leir—he also added several elements that were wholly original to the story of King Lear. Jay Halio notes that Shakespeare “introduced several new characters and episodes that King Leir lacks, such as Lear’s madness, the storm, Oswald, and the Fool (who may, however, have been suggested by the Gallian King’s jesting companion, Mumford, in King Leir)” (Halio 3).[vi] The tragic ending is also an addition of Shakespeare’s, as his version of the story would foreground Cordelia’s death and present it, for the first and only time, as a murder rather than a suicide. In every one of Shakespeare’s potential sources, the play ends on what must be considered a “happier” note. In all four source texts, Cordelia either explicitly (Monmouth, Holinshed, and Spenser) or implicitly (Leir) proceeds to inherit her father’s kingdom and rule for a span of years. While Cordelia’s eventual death is tragic, it is tragedy deferred, and generally presented as a tragic piece of a larger narrative of English monarchy, a narrative that would then lead to idyllic periods in England’s pseudo-history, including the reign of King Arthur and the Tudor/Stuart monarchs. The conclusion of Shakespeare’s version of the play is distinctly tragic in a way that the others were not, due to the immediacy of that tragedy and the all-consuming scope represented therein.[vii]

Though Shakespeare added a professional fool and a darkly tragic conclusion, neither element was retained by the next iteration of the Lear story. From 1681 to 1838, the Fool didn’t turn up at all. Shakespeare’s version of the play was effectively off the stage, and it was the revision of Nahum Tate that became associated with the name of Lear. In Tate’s version, Edmund opens the action alone, in a monologue of ill intent evocative of Richard III. The love test in the opening act is more duplicitous on all parts, as Lear uses it to try and trick Cordelia into marrying his choice of husband. Cordelia intentionally angers her father in the hopes that he will then let her marry Edgar, and Goneril and Regan manipulate both parties in order to seize control of the kingdom (1.1.92-126). Lear still disowns Cordelia, though he doesn’t banish her. Other changes include a love plot between Cordelia and Edgar, an uprising of the peasants rather than an invasion from France (4.1.33-44), and a legitimately happy ending, with Gloucester proclaiming a “second birth of empire” and celebrating his son’s revelation of “the king’s blest restoration” (5.6.116-118). Lear does not reclaim the throne in Tate’s play, but rather chooses to retire “to some cool cell” and reflect on past fortunes with Kent and Gloucester while they revel in what they assume will be the “prosperous reign” of the “celestial pair”—Cordelia and Edgar (5.6.146-153).[viii]

Tell me what you know about King Lear.

As with so much of Shakespeare, the story of King Leir/Lear had been told several times before its appearance on the Globe stage. Geoffrey of Monmouth is credited with the earliest version, in his 12th century work, Historia regum Britanniae, a pseudo-historical text that constructed a continuous narrative between the legendary founder of Britain—Brutus, the grandson of the Trojan hero Aeneas—and, in effect, the Tudor/Stuart monarchs.[i] Monmouth’s version of Lear opens with the love contest, but none of Lear’s daughters are at that point married. After being spurned by his youngest child’s modesty, Lear proceeds to give only half of his kingdom to his elder daughters and their husbands, retaining the other half for himself until the time of his death (Geoffrey 82). Being impatient, his sons-in-law rebelled to secure the other half of the kingdom, deposing Lear (Geoffrey 83). With the help of his youngest daughter, Lear regains the throne and rules for another three years. At that point, Cordelia inherits the entirety of Britain, and rules peacefully for five years.

In many later versions of the story, this is where the plot ends, with Lear or Cordelia happily on the throne of a peaceful, united Britain. In Monmouth’s text, however, Cordelia’s nephews Marganus and Cunedagius, rebel against their aunt due to her being a woman ruler (Geoffrey 86). They imprison Cordelia, who “grieved more and more over the loss of her kingdom and eventually...killed herself” (Geoffrey 87). Her misogynistic nephews prove unable to share, however, and war against each other until Cunedagius kills his cousin and rules the whole of Britain peacefully for thirty-three years (Geoffrey 87).

The post-divestiture winnowing of Lear’s train was likely a borrowing from Raphael Holinshed’s version of the Lear story. Shakespeare almost certainly saw Holinshed’s version in the 1587 second edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles, which opens the story in much the same way as Monmouth: Lear engages in the love test, disowns his youngest child, marries off his elder daughters, and gives them each a quarter of the kingdom in dowry (Holinshed). Lear again reserves half the kingdom for himself while he lives, and his sons-in-law, Maglanus and Henninus, again rebel and seize Lear’s half for themselves. In Holinshed, however, we see Lear held by his sons-in-law, and “put to his portion, that is, to liue after a rate assigned to him for the maintenance of his estate, which in processe of time was diminished” by both of his would-be-heirs (Holinshed). Lear and Cordelia war against the usurpers, slaying Maglanus and Henninus, restoring Lear to the throne (Holinshed). The story continues from there as it had in Monmouth, with Cordelia ruling for five years after her father’s death before being deposed by her nephews and committing suicide in prison.

The version of the Lear narrative contained in Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (c. 1590) likely provided Shakespeare with the method of Cordelia’s death—hanging. Spenser’s version dispenses with Lear’s retention of half the kingdom and has him disown Cordelia, sharing his entire kingdom “twixt the other twain” (Spenser 166). Rather than the riotous knights in Shakespeare’s version, Spenser’s Lear sought to lead a private life in Albania (Scotland) with Gonoril (Spenser 166). Again, the elder daughters and their husbands scorn the former king, and again he goes to Cordelia who, through armed conflict, restores her father to the throne. Spenser’s addition to the post-script of the Lear narrative is the manner of Cordelia’s eventual suicide, as he is the first to indicate that “kept in prison long, / Till weary of that wretched life, her selfe she hong” (Spenser 167).

Oddly enough, the version that Shakespeare was most likely to have encountered—the anonymous King Leir--is the one least like his own.[ii] This version of the story features more blatantly villainous daughters—Regan hires a murderer to kill her father and his old friend Perillus after arranging to meet them in a thicket “some two miles from the court” (1.17.7-56).[iii] Even with more naked villainy than its predecessors, King Leir feels less threatening. There are comedic characters added to the plot, including disreputable sailors, a vice figure who is talked out of murder, and Mumford—a companion to the Gallian king—who seems almost obsessively focused on bedding any English woman. The play, as was common for Queen’s Men’s productions, was also clearly meant to serve as propaganda for Queen Elizabeth I. There are several scenes wherein the icons of her narrative of rulership are referenced to construct a thinly-veiled identification between Elizabeth and Cordelia. The French King calls Cordelia “Mirror of virtue. Phoenix of our age! / Too kind a daughter for an unkind father!” (1.16.46-47).[iv] With this connection between Cordelia and Elizabeth, it is no surprise that King Leir omits the part of the story wherein Cordelia is imprisoned by her nephews until her ultimate suicide. Instead, the play gives Leir the last speech, where he thanks all, culminating with the amorous Mumford who “lion-like” chased away Leir’s elder daughters and their husbands. The final words of the play are directed to Cordelia and the French King: “Come, son and daughter, who did me advance; / Repose with me awhile, and then for France” (1.29.175-176). Though the play—as per some of the earlier versions—suggests the possibility for tragedy, there is no element of tragedy represented in the conclusion at all. In King Leir, even the villains survive. This also marks the point where, Shakespeare’s text aside, retellings of the Lear story would begin going to great lengths to omit the detail of Cordelia’s delayed death.[v]

While Shakespeare sourced several elements of his Lear from earlier versions—the love contest and Cordelia’s imprisonment from Monmouth, the winnowing of the train from Holinshed, the hanging of Cordelia and Lear’s complete divestment from Spenser, and the humor from Leir—he also added several elements that were wholly original to the story of King Lear. Jay Halio notes that Shakespeare “introduced several new characters and episodes that King Leir lacks, such as Lear’s madness, the storm, Oswald, and the Fool (who may, however, have been suggested by the Gallian King’s jesting companion, Mumford, in King Leir)” (Halio 3).[vi] The tragic ending is also an addition of Shakespeare’s, as his version of the story would foreground Cordelia’s death and present it, for the first and only time, as a murder rather than a suicide. In every one of Shakespeare’s potential sources, the play ends on what must be considered a “happier” note. In all four source texts, Cordelia either explicitly (Monmouth, Holinshed, and Spenser) or implicitly (Leir) proceeds to inherit her father’s kingdom and rule for a span of years. While Cordelia’s eventual death is tragic, it is tragedy deferred, and generally presented as a tragic piece of a larger narrative of English monarchy, a narrative that would then lead to idyllic periods in England’s pseudo-history, including the reign of King Arthur and the Tudor/Stuart monarchs. The conclusion of Shakespeare’s version of the play is distinctly tragic in a way that the others were not, due to the immediacy of that tragedy and the all-consuming scope represented therein.[vii]

Though Shakespeare added a professional fool and a darkly tragic conclusion, neither element was retained by the next iteration of the Lear story. From 1681 to 1838, the Fool didn’t turn up at all. Shakespeare’s version of the play was effectively off the stage, and it was the revision of Nahum Tate that became associated with the name of Lear. In Tate’s version, Edmund opens the action alone, in a monologue of ill intent evocative of Richard III. The love test in the opening act is more duplicitous on all parts, as Lear uses it to try and trick Cordelia into marrying his choice of husband. Cordelia intentionally angers her father in the hopes that he will then let her marry Edgar, and Goneril and Regan manipulate both parties in order to seize control of the kingdom (1.1.92-126). Lear still disowns Cordelia, though he doesn’t banish her. Other changes include a love plot between Cordelia and Edgar, an uprising of the peasants rather than an invasion from France (4.1.33-44), and a legitimately happy ending, with Gloucester proclaiming a “second birth of empire” and celebrating his son’s revelation of “the king’s blest restoration” (5.6.116-118). Lear does not reclaim the throne in Tate’s play, but rather chooses to retire “to some cool cell” and reflect on past fortunes with Kent and Gloucester while they revel in what they assume will be the “prosperous reign” of the “celestial pair”—Cordelia and Edgar (5.6.146-153).[viii]

Ian Holm Lear:

Kozintsev Lear:

Court as center of power vs. court as center of symbolic identity

King of Earth Kingdom vs. Fire Lord

Before Restoration of the throne. After Restoration of the throne